Africa

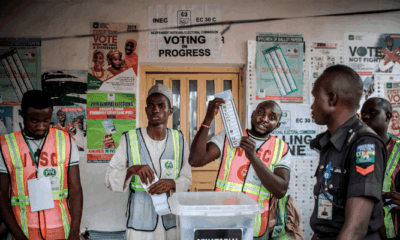

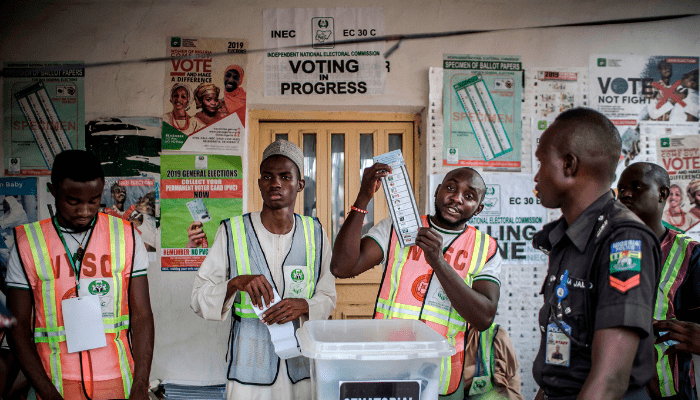

Nigeria’s Elections: Tipex and E-Transmission -By Prince Charles Dickson Ph.D

The irony is striking: The same Nigeria that conducts multimillion-dollar oil transactions digitally now doubts whether it can upload a simple jpeg of a polling unit result sheet. The same country that uses BVN, NIN, e-passport, online tax filing, and global remittances suddenly becomes confused about digital results transmission.

How many times can a nation rewrite its own ballot before its people stop believing in ink?

How long can democracy survive on correction fluid and excuses disguised as reforms?

These are not idle questions. They sit at the heart of Africa’s most populous country, a nation that keeps insisting on greatness but keeps rewarding mediocrity in its most important ritual: elections.

In 2019, Malawi taught the continent an unforgettable lesson. A court; bold, unblinking, unafraid, nullified a presidential election after discovering that results sheets had been altered with ordinary Tipp-Ex. Yes, corrector fluid, the kind students use to fix spelling mistakes. Political operatives seized tally sheets, manually edited figures, and returned them as “official results.” Malawians called it “the Tipp-Ex Election.” And they called the president “the Tipp-Ex President.”

The world laughed. Then it paused. Because behind the humour was a sobering truth: the tools may differ; Tipp-Ex, pen, server shutdowns, “technical glitches,” delayed uploads, over-voting, and suspicious cancellations, but the intention is the same: manipulate the people’s will.

So, the question for Nigeria becomes painfully simple:

If Tipp-Ex could bring down an election in Malawi, what will bring down electoral credibility in Nigeria — or has it happened already?

Nigeria is currently wrestling with the politics of e-transmission of results. A country that prides itself on innovation, fintech, and global tech dominance suddenly becomes cautious, almost allergic, when technology enters the one place where transparency is needed most: elections.

We boldly move billions through digital rails, transfer money across states in seconds, pay school fees online, run businesses on apps, track deliveries in real time, but when it comes to votes, the heartbeat of democracy, the system develops hypertension.

Why?

Because technology does not fear politicians.

Technology does not understand “structure.”

Technology cannot be intimidated by incumbency. Technology does not take bribes.

Technology does not know party agents. Technology records what it sees.

That is the real fear.

Malawi’s story is a mirror held up to the continent. It reminds us that election rigging is rarely sophisticated. Sometimes it is crude. Physical. Embarrassingly analog. But it also shows what judicial courage can correct. The High Court of Malawi did not say “go and complain to God.” It said bring evidence. And when the Tipp-Ex bottles began to surface, the truth became unavoidable.

Now, imagine if Malawi had e-transmission in 2019. Imagine if every polling unit result was uploaded instantly. Imagine if alteration became impossible because there was no sheet to grab, no figure to smudge, no ink to dilute.

Would Malawi have avoided the Tipp-Ex shame? Almost certainly.

Nigeria’s arguments against e-transmission often come wrapped in the language of concern, but scratch the surface and it reveals something less noble.

We are told: “Network coverage is poor.” But banks run real-time digital operations in the same communities. We are told: “Technology can fail.” But manual systems fail every election cycle; often conveniently.

We are told: “It can be hacked.” Yet the absence of technology ensures one thing: elections can be freely hacked by humans without any trace.

We are told: “Let’s be cautious.” But caution has produced elections dripping with suspicion, litigation, and nationwide cynicism.

E-transmission is not a miracle cure. It will not transform Nigeria into Sweden by the next election. But what it offers is evidence, speed, and transparency, three things the political class fears more than opposition rallies.

Underneath the debate lies a deeper national issue: Nigeria does not have a technology problem. It has a trust problem. People do not trust INEC. INEC does not trust politicians.

Politicians do not trust each other. And Nigerians do not trust the system at all.

So, any reform, no matter how logical, becomes a battlefield.

The irony is striking: The same Nigeria that conducts multimillion-dollar oil transactions digitally now doubts whether it can upload a simple jpeg of a polling unit result sheet. The same country that uses BVN, NIN, e-passport, online tax filing, and global remittances suddenly becomes confused about digital results transmission.

It is not logical. It is politics.

Readiness is not a technical question. It is a political one. Technically, Nigeria has the capacity. Politically, Nigeria has the resistance.

But history is unkind to nations that fear progress. E-transmission is not even cutting-edge anymore. It is the bare minimum for credibility.

The deeper question is this: What is Nigeria afraid of losing, or who is afraid of losing, if polling unit results become instantly visible nationwide?

In a country where elections are often decided long before ballot papers arrive, transparency becomes a threat. Real-time transmission collapses the room where “figures are harmonised,” “margins are reconciled,” and “over-voting is adjusted.”

It kills the corridor politics that thrives between polling units and collation centres. It reduces the oxygen available for rigging.

And that is why the debate continues.

The world is moving forward. The continent is evolving. Even authoritarian governments now use technology to show minimal transparency because legitimacy matters.

Nigeria cannot cling to old tools and expect new outcomes. It cannot run a democracy with analog methods and expect digital trust.

The question is not whether e-transmission is perfect. The question is whether the alternative; the Tipp-Ex mentality is acceptable.

Malawi rejected it. Kenya challenged it. Sierra Leone tested transparency. Ghana used parallel vote tabulation. South Africa broadcasts results live.

Where is Nigeria in this story?

It is because every election is a mirror. It reflects not just votes but values. Nigeria’s elections have become a reflection of unresolved fears, institutional fragility, and a political class that wants progress without accountability.

But democracy is a jealous system. It demands courage. It demands transparency. It demands that nations outgrow their excuses. The Tipp-Ex era belongs to a past that should embarrass any modern state. E-transmission belongs to a future that Nigeria cannot afford to run away from.

So, the real question becomes: Will Nigeria choose the path of courage like Malawi, or continue choosing correction fluid over correctional justice? Will we cling to paper that can be erased or embrace technology that remembers?

The answer, whenever it finally comes, will decide the credibility of Nigeria’s democracy and its future—May Nigeria win!