Forgotten Dairies

Opposition Persecution And The Nigeria’s Multiparty Democracy -By Ibrahim Mustapha Pambegua

For Nigeria to sustain its democratic experiment, the rule of law must be transparent, impartial, and consistent. Anti-graft agencies must demonstrate that their actions are guided solely by evidence and due process, not by political calculations. Equally important, political leaders must resist the temptation to weaponize state power against rivals. Ultimately, the burden lies on the federal government to reassure citizens that Nigeria is not drifting toward a one-party state.

As the 2027 general elections draw nearer, Nigeria’s political space is becoming increasingly tense.Leaders of opposition parties have raised alarm over what they describe as systematic political persecution by the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC). These concerns have emerged alongside a wave of defections by governors and lawmakers from opposition parties to the APC, allegedly under pressure or intimidation. The development has triggered serious debate about the fate of Nigeria’s multiparty democracy.

Democracy thrives only in an atmosphere of competition. When opposition voices are weakened or silenced, governance becomes less accountable and citizens’ choices are narrowed.

Since assuming office, Bola Ahmed Tinubu has been accused by opposition leaders of attempting to edge Nigeria toward a one-party state. The APC has dismissed these claims as propaganda, insisting that defections are voluntary and motivated by ideological alignment. Yet recent events have added weight to the fears expressed by critics.

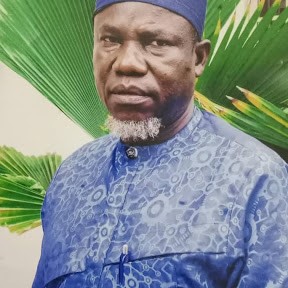

Central to the controversy is the arrest and continued detention of former Attorney-General and Minister of Justice, Abubakar Malami. Despite being granted bail by a court, Malami was reportedly re-arrested and remains in custody over allegations of money laundering, illegal possession of arms, and terrorism financing. While the government argues that the prosecution is based strictly on legal grounds, many Nigerians believe the case is politically motivated.

Malami served prominently in the Buhari administration and belongs to the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC) bloc within the APC. This bloc, which includes former Kaduna State governor Nasiru El-Rufai, has complained of being sidelined after President Tinubu’s victory in 2023. The situation is further complicated by speculation that Malami harbours gubernatorial ambitions in Kebbi State.

In Nigeria’s political culture, ambition is often enough to attract suspicion and scrutiny, especially when it threatens established power structures.

Before public anxiety over Malami’s ordeal could subside, another dramatic episode unfolded involving Nasiru El-Rufai. Upon returning from Egypt, El-Rufai alleged that Department of State Security,DSS attempted to arrest him at the Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport, Abuja. In interviews with BBC Hausa and ARISE TV, he explained that he had earlier received an invitation from the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) while abroad. However, he accused the National Security Adviser of directing the Department of State Services (DSS) to arrest him without a valid court order.

In a further twist, the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) also invited El-Rufai for questioning. Through his lawyers, the former governor has confirmed his intention to honour the invitation and clear his name. His response underscores a key point: there is nothing inherently wrong with investigating or prosecuting any former public official, provided the process follows the rule of law and respects constitutional safeguards.

The real concern lies not in the existence of investigations but in their perception and timing. Why are these actions occurring just as political alignments for 2027 are taking shape? Why do they appear to disproportionately affect individuals associated with opposition politics or disenchanted blocs within the ruling party? These questions are not easily dismissed, especially in a country with a history of using state institutions to settle political scores. Nigeria’s anti-corruption agencies were created to uphold justice, not to serve as instruments of intimidation. When arrests and invitations are seen as selective or politically driven, public trust in these institutions erodes.

Worse still, the opposition begins to view every prosecution as persecution, and every court case as a political battle.This blurring of lines between law enforcement and politics weakens democracy itself. The timing of these events is particularly troubling.With the 2027 elections approaching, Nigerians fear that more opposition figures may face similar ordeals. If this pattern continues, the political field may be skewed long before voters reach the ballot box. A democracy without a viable opposition is little more than a façade.

For Nigeria to sustain its democratic experiment, the rule of law must be transparent, impartial, and consistent. Anti-graft agencies must demonstrate that their actions are guided solely by evidence and due process, not by political calculations. Equally important, political leaders must resist the temptation to weaponize state power against rivals. Ultimately, the burden lies on the federal government to reassure citizens that Nigeria is not drifting toward a one-party state. Democracy flourishes when dissent is protected, competition is fair, and justice is opening to everyone no matter whose ox is gored. Anything short of this risks replacing political debate with fear and transforming legitimate law enforcement into a tool of repression. As the nation inches toward another critical election cycle, the question remains: will Nigeria deepen its democratic culture, or will it slide into a politics of exclusion and intimidation? The answer will be found not only in official statements, but in how power is exercised—and how the opposition is treated—in the months ahead.

Ibrahim Mustapha Pambegua, Kaduna State. 08169056963.