Africa

Black History Month: Honoring the Past While Challenging African Continental Leadership -By Prof. John Egbeazien Oshodi

The therapeutic path forward begins with humility—leaders acknowledging that power is temporary but responsibility is permanent. Nations heal when leaders listen before they command, serve before they accumulate, and build institutions stronger than themselves. Citizens also must reclaim their voices, demand accountability peacefully, and invest in community rebuilding rather than surrendering to despair.

The Tragedy of Leaders Who Forgot Their Own People

Black History Month in America is not merely a celebratory ritual; it stands as a global moral summons demanding accountability from all who claim leadership over Black populations worldwide. Yet across much of the African continent, too many leaders—the modern “Little Kings” and “Little Queens”—have psychologically distanced themselves from the very people and heritage they are meant to serve. They enthusiastically commemorate foreign anniversaries, seek Western approval, and echo imported political language, yet consistently fail to build societies that guarantee dignity, justice, and genuine opportunity for their own citizens.

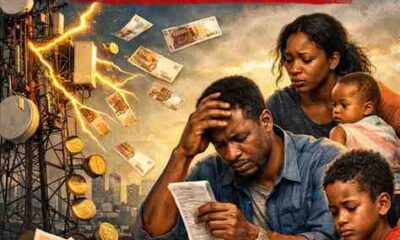

This disconnection is not accidental. It reflects a deeper psychological surrender: a leadership class that has subconsciously internalized the idea that progress must be approved from outside Africa. Black History Month becomes, in their minds, an American affair rather than a global reminder of shared struggle, resilience, and collective destiny. While citizens suffer under economic hardship, insecurity, and institutional collapse, these leaders remain intoxicated by proximity to Western approval rather than proximity to their own people’s suffering. That betrayal is not merely political; it is psychological abandonment.

Mental Colonization: The Silent Crisis Destroying Governance

The most painful truth is that many African leaders no longer believe in African solutions. They operate as administrators of borrowed systems rather than architects of indigenous progress. Village wisdom, communal responsibility, ancestral moral codes, and indigenous governance traditions are dismissed as primitive while foreign prescriptions are blindly adopted without adaptation.

The result is confusion. Institutions become hollow replicas of Western models lacking local legitimacy or cultural grounding. Laws are copied but not respected. Systems exist on paper but collapse in practice. Governance becomes performance rather than service. Leadership becomes entitlement rather than stewardship.

This mental colonization produces leaders who behave not as custodians of public trust but as rulers of personal empires. Ministries become patronage centers. Public funds become private inheritance. Elections become contests of manipulation rather than visions for progress. Citizens become spectators instead of stakeholders. And once power is tasted, many leaders transform into small despots guarding privilege rather than protecting people.

When Power Becomes Personal: The Rise of the “Little Kings and Queens”

The tragedy deepens when public institutions lose their collective purpose. Leadership shifts from nation-building to ego-protection. Offices become thrones. Criticism becomes treason. Opposition becomes an enemy rather than democratic necessity.

These “Little Kings” and “Little Queens” personalize power, weaponize institutions, and weaken democratic structures to secure personal dominance. Security forces are sometimes deployed not to protect citizens but to intimidate them. Courts are pressured. Legislatures become rubber stamps. Governance devolves into personality cults rather than constitutional responsibility.

Such leaders do not see citizens as partners in development but as subjects to be controlled. Public wealth becomes political currency. Youth become tools for electoral violence. And national conversations are reduced to tribal, religious, or partisan divisions rather than collective national growth.

The deeper issue, however, is psychological insecurity. Leaders uncertain of their legitimacy cling to power through force, manipulation, or foreign alliances rather than competence and service. This insecurity reveals leaders who fear their own people instead of serving them.

Psychoafricalysis: Ending the Psychology of Dependence

Psychoafricalysis challenges this cycle at its root—the psychology of dependence and internalized inferiority. The framework insists that healing Africa requires psychological liberation alongside economic and political reform.

True leadership demands psychological confidence rooted in African identity, history, and communal values. African civilizations governed complex societies long before colonial disruption. Indigenous conflict resolution systems preserved peace. Community-centered governance emphasized accountability. These traditions are not relics; they are foundations waiting to be modernized and reintegrated.

The continent does not need imitation leadership. It needs leaders courageous enough to believe in African potential, capable of adapting global knowledge without surrendering local identity, and humble enough to serve rather than dominate. Psychological independence must replace validation-seeking behavior. Leadership must become service again.

A Therapeutic Call: Healing Leadership, Healing Nations

Yet, even in critique, healing remains possible. Psychoafricalysis does not seek to condemn without offering recovery. Leadership, like individuals, can heal when confronted with truth and guided toward self-reflection.

The therapeutic path forward begins with humility—leaders acknowledging that power is temporary but responsibility is permanent. Nations heal when leaders listen before they command, serve before they accumulate, and build institutions stronger than themselves. Citizens also must reclaim their voices, demand accountability peacefully, and invest in community rebuilding rather than surrendering to despair.

Healing requires collective psychological restoration: teaching young Africans pride in their identity, restoring trust in institutions through transparency, and cultivating leaders who measure success by the wellbeing of citizens rather than personal wealth or foreign praise.

Africa’s future does not lie in endless dependency or borrowed identities. It lies in psychological confidence, institutional reform, and communal solidarity. Black History Month must remind both leaders and citizens that our ancestors endured slavery, colonization, and exploitation yet preserved dignity and resilience. Their legacy demands not submission, but renewal.

The continent does not need “Little Kings” and “Little Queens.” It needs servant leaders, psychologically liberated citizens, and institutions grounded in collective dignity.

And therapeutically, we must remember: healing begins not by denying wounds, but by confronting them honestly and choosing transformation over resentment. Africa’s story is not finished. The next chapter remains ours to write—with courage, clarity, and collective healing.

About the Author

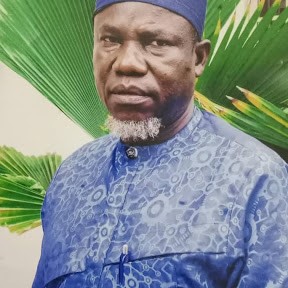

Prof. John Egbeazien Oshodi is an American psychologist, an expert in policing and corrections, and an educator with expertise in forensic, legal, clinical, and cross-cultural psychology, including public ethical policy. A native of Uromi, Edo State, Nigeria, and son of a 37-year veteran of the Nigeria Police Force, he has long worked at the intersection of psychology, justice, and governance. In 2011, he helped introduce advanced forensic psychology to Nigeria through the National Universities Commission and Nasarawa State University, where he served as Associate Professor of Psychology.

He teaches in the Doctorate in Clinical and School Psychology at Nova Southeastern University; the Doctorate Clinical Psychology, BS Psychology, and BS Tempo Criminal Justice programs at Walden University; and lectures virtually in Management and Leadership Studies at Weldios University and ISCOM University. He is also the President and Chief Psychologist at the Oshodi Foundation, Center for Psychological and Forensic Services, United States.

Prof. Oshodi is a Black Republican in the United States but belongs to no political party in Nigeria—his work is guided solely by justice, good governance, democracy, and Africa’s development. He is the founder of Psychoafricalysis (Psychoafricalytic Psychology), a culturally grounded framework that integrates African sociocultural realities, historical awareness, and future-oriented identity. He has authored more than 500 articles, multiple books, and numerous peer-reviewed works on Africentric psychology, higher education reform, forensic and correctional psychology, African democracy, and decolonized models of clinical and community engagement.