Africa

Compulsory Voting: A Democratic Boost Or A Backdoor To Authoritarianism? Lessons From Australia, Belgium, And Brazil -By Isaac Asabor

True democracy does not grow by force, but by faith, faith in the system, faith in leadership, and faith that one’s voice truly matters. Until that faith is restored, compulsory voting in Nigeria will remain a misguided solution to a misunderstood problem.

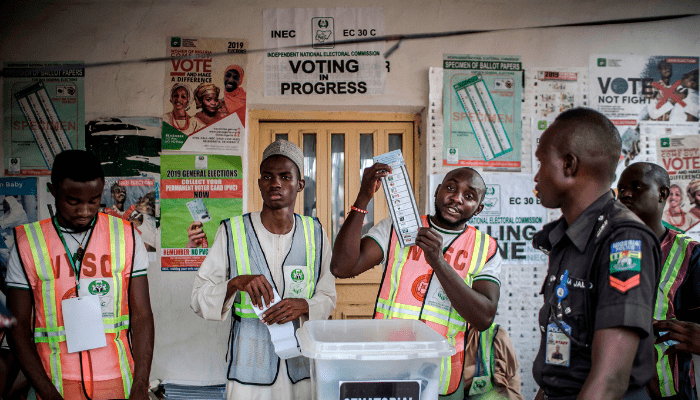

Since the move to pass a bill mandating all Nigerians of voting age to participate in every election or face a six-month jail term or a fine of ₦100,000, debates have flared across the country’s political and civic spaces. Surprisingly, what many initially perceived as a draconian proposal has begun to attract support from certain influential and seemingly enlightened Nigerians. Prominent among them are Honourable Benjamin Kalu, Deputy Speaker of the House of Representatives, and Barrister Monday Ubani, a respected legal practitioner and human rights advocate.

Both men, in separate interviews and public engagements, have attempted to sell the democratic value of the bill. Their argument rests on the premise that compulsory voting will enhance democratic participation, strengthen legitimacy of elected officials, and reduce the apathy that has plagued Nigeria’s electoral system for decades. Kalu even described the bill as a step toward deeper democratic engagement, while Ubani stated that the bill, once passed into law, would “instill civic responsibility.”

At first glance, these arguments might sound logical, and perhaps even idealistic, but a deeper examination reveals that compelling citizens to vote under threat of imprisonment or financial punishment may, in fact, undermine the very democratic ideals it purports to uphold.

In fact, the very idea of democracy is built on freedom which cut across freedom of speech, freedom of association, and yes, freedom to abstain. While voting is a civic duty, it is not a moral crime to choose not to engage, especially in an environment like Nigeria where trust in political actors is historically low and where votes do not count.

By proposing jail terms and heavy fines for non-voters, the Nigerian bill introduces a coercive element that is fundamentally at odds with democratic liberty. Unlike Australia, Belgium, and Brazil, countries that have long-standing civic structures, efficient institutions, and robust democratic norms, Nigeria’s socio-political environment is too fragile to absorb such authoritarian undertones in the guise of civic duty.

Without a doubt, democracy must persuade, not compel. To truly grasp this argument, it is germane to draw the global comparison, and understand what the data says. Let us examine how countries with compulsory voting laws have fared; namely Australia, Belgium, and Brazil.

Australia, where voting has been mandatory since 1924, boasts around 90% turnout. However, non-voters face only a modest fine (about AUD 20), and there is an option to submit a valid reason for abstention.

Belgium, one of the earliest adopters of mandatory voting, enforces stricter penalties. Still, it provides extensive civic education and has invested in political literacy programs to make voting more meaningful.

Brazil includes the option of voting as a civic right, not just a duty, and enforces participation through minor penalties like fines or administrative restrictions (e.g., access to public employment).

But here is the catch: all three countries have invested heavily in civic education, political accountability, transparent electoral processes, and institutional trust, areas where Nigeria continues to struggle.

Simply copying their laws without mirroring their social infrastructure is not only lazy legislation, it is dangerous.

Analyzing the issue from the perspective of the Nigerian reality, particularly given the factors of broken trust and political alienation, it is not out of place to opine that supporters of the Nigerian bill, like Kalu and Ubani, ignore a brutal truth: many Nigerians do not vote because they no longer believe their votes count. This is not mere laziness or irresponsibility, it is political trauma born from decades of electoral fraud, ballot snatching, vote-buying, rigging, and judicial interference.

How can one mandate participation in a system that so many see as compromised? Without first fixing the root of electoral apathy, namely corruption, inefficiency, and disenfranchisement, compulsory voting only becomes a tool of state bullying rather than civic reform.

Imagine a young Nigerian, jobless, disillusioned, and disempowered, being jailed or fined ₦100,000 for refusing to vote in an election he or she believes is predetermined. How is that democracy?

Hon. Kalu’s endorsement of this bill might be well-meaning, but the risk of selective enforcement in Nigeria’s current political climate cannot be overlooked.

In a country where enforcement of laws often follows political, ethnic, or religious lines, compulsory voting can quickly become a political weapon. Who gets punished? Who gets exempted? Who ensures fairness? The law, if passed, could easily become another channel for state oppression, particularly against the poor, opposition strongholds, or disenfranchised communities.

Look at the law through the prism of ethical dilemma: it is expedient to opine that voting is a right, not a chore.

Another flaw in the pro-compulsion argument is the moral disservice it does to democratic engagement. If people are voting under duress, the quality of votes deteriorates. This has been seen even in the most advanced compulsory voting systems: In Australia, a significant portion of voters cast “donkey votes” (voting in the order candidates appear on the ballot, regardless of choice). In Brazil, protest votes or intentionally spoiled ballots are common. In Belgium, blank voting is used to comply without truly participating.

If Nigeria enforces voting by force without political education, many ballots will simply become a meaningless tick or a blank protest.

Given the foregoing, the question is, “What should be done instead?” If Hon. Kalu, Barrister Ubani, and other supporters of the bill truly desire greater democratic participation, there are more democratic, and sustainable ways to achieve it. The ways cut across the carrying out of massive civic education, electoral reform, incentivized voting, and transparent leadership.

Comprehensively put, there is an urgent need for Nigerians to be taught the value of their vote, not threatening them into using it.

In a similar vein is the need for the elimination of vote-rigging, and ensuring real-time result transmission, and holding electoral offenders accountable.

Also in a similar vein, instead of punishment, there is the need to explore modest, ethical incentives, such as tax credits, or recognition for active civic participation.

Again, if leaders perform, trust builds, and with trust comes voluntary turnout.

Until these systemic reforms are in place, compulsory voting in Nigeria will not solve anything. It will only paper over cracks in a foundation that is already shaky.

While countries like Australia, Belgium, and Brazil may serve as models in increasing electoral participation through compulsory voting, context matters. These countries had the institutions, transparency, and democratic culture in place before enforcing such laws. Nigeria, on the other hand, still grapples with foundational democratic issues, like voter suppression, rigged elections, judicial compromise, and gross inequality.

By pushing for a compulsory voting law backed by jail terms or ₦100,000 fines, Hon. Benjamin Kalu and Monday Ubani may have lost sight of the core essence of democracy, which is unarguably choice.

True democracy does not grow by force, but by faith, faith in the system, faith in leadership, and faith that one’s voice truly matters. Until that faith is restored, compulsory voting in Nigeria will remain a misguided solution to a misunderstood problem.