Politics

If “Agreement Is Agreement,” Why Must The Public Guess? Are Riverians And Nigerians Not Owed The Truth In A Democracy? -By Isaac Asabor

The situation in Rivers State therefore presents an opportunity as much as it presents a challenge. It is an opportunity for those in authority to reaffirm a foundational democratic principle: that public office is exercised openly, in trust, and with respect for the people’s right to know. It is an opportunity to replace speculation with clarity and suspicion with confidence.

When a public official repeatedly insists that “Agreement is agreement,” the phrase may sound firm, even principled. But in a democratic society, such a declaration cannot stand alone. Agreements that influence governance are not private whispers between political actors; they are matters that can shape institutions, public resources, and the lives of millions. That is why the persistent invocation of an undefined “agreement” in the unfolding political drama in Rivers State raises a question that cannot be dismissed as mere political curiosity. It is a question rooted in democratic legitimacy: if power is exercised in the name of the people, are the people not entitled to know the terms under which that power operates?

Recent developments intensify this concern. Governor Siminalayi Fubara’s decision to dissolve his cabinet and appoint a new Chief of Staff widely believed to be aligned with his predecessor has not merely reshuffled administrative roles; it has reshaped the political conversation. Observers are not simply asking what changed, but why it changed, and under whose influence. The move, occurring against a backdrop of sustained political tension, has reinforced the perception that governance in the state may be unfolding within the boundaries of an understanding that remains undisclosed to the very citizens whose mandate underpins the government’s authority.

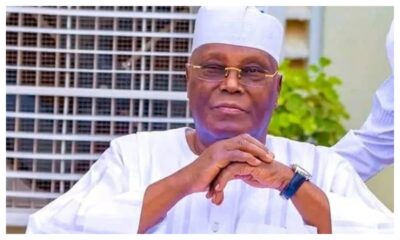

At the center of this controversy stands Nyesom Wike, whose repeated emphasis on the sanctity of an “Agreement” has transformed a political catchphrase into a constitutional dilemma. Agreements in politics are not inherently suspicious. Alliances, negotiations, and strategic partnerships are natural features of democratic competition. Political mentorship is not a violation of public trust. Continuity of influence is not automatically illegitimate. What becomes problematic, however, is opacity. When an agreement is invoked as a guiding force behind public decisions but its content remains undisclosed, citizens are effectively asked to accept consequences without explanation.

Democracy does not function through ritual elections alone. Elections confer authority, but transparency sustains legitimacy. Citizens vote not merely for personalities but for accountable governance. The moment public decisions appear to be anchored in private commitments whose scope is unknown, the democratic contract weakens. Rivers people did not vote for an undisclosed arrangement; they voted for leadership that would act visibly and responsibly in their name.

The dissolution of a cabinet is, in itself, a lawful exercise of executive power. Governors reorganize administrations to improve efficiency, assert authority, or pursue new policy directions. But context matters. When such a sweeping move coincides with narratives of external influence, silence ceases to be neutral. Silence becomes interpretive space, and in politics, interpretation quickly becomes suspicion.

This is not merely about political rivalry or personal loyalty. It is about the structural integrity of governance. Public office demands that decisions affecting state administration be justified in terms of public interest, not personal obligation. When a governor’s actions appear to reflect fidelity to an unseen understanding, the distinction between public duty and private allegiance becomes blurred. That blur does not merely affect perception; it affects confidence, and confidence is the currency of democratic stability.

The language of “agreement” also introduces a troubling conceptual shift. It suggests that political authority may be contingent not solely on constitutional mandate but on prior commitments whose terms are not subject to public scrutiny. If that interpretation holds, governance risks becoming transactional rather than representative. Leadership would then be shaped less by public accountability and more by private compliance. That is a transformation no democratic system can accommodate without consequence.

It is important to recognize the broader implications. Rivers State is not politically peripheral. Its economic significance, strategic location, and role in national revenue generation give its governance national resonance. Decisions taken within its executive chambers do not remain confined within state boundaries; they ripple across the federation. Consequently, the people of Nigeria also have a legitimate stake in the clarity of authority within the state.

Transparency in such a context is not an abstract virtue; it is a stabilizing mechanism. When citizens understand the basis of political decisions, even controversial actions can be debated within a framework of trust. When they do not, speculation fills the vacuum. Speculation breeds polarization. Polarization weakens institutions. This chain reaction does not require dramatic events to unfold; it emerges gradually from sustained uncertainty.

The recurring assertion that “agreement is agreement” therefore demands clarification not because citizens are hostile to political compromise, but because democracy requires informed consent. Consent cannot exist where knowledge is withheld. A government that expects obedience without explanation does not strengthen authority; it strains it.

Some may argue that political arrangements often operate behind the scenes and that public disclosure of every understanding is unrealistic. That argument, while superficially pragmatic, misses the essential distinction between strategy and control. Political negotiation is inevitable, but governance must remain visibly autonomous. If an agreement merely reflects mutual respect between political actors, disclosure would not threaten it. If it defines the operational boundaries of an elected administration, then secrecy becomes incompatible with democratic norms.

Governor Fubara’s position is particularly significant. He occupies office through an electoral mandate that is independent in law, even if influenced in politics. The authority of that mandate cannot be perceived as conditional without eroding its meaning. When executive decisions align closely with perceived expectations of a predecessor, the governor’s autonomy becomes a public question. Autonomy, in democratic governance, is not a personal privilege; it is an institutional necessity.

Equally, those who wield influence outside formal office must recognize the limits of political legacy. Influence earned through leadership does not translate into perpetual authority. Democratic succession is not symbolic; it is substantive. Once power transfers, accountability transfers with it. To suggest otherwise, implicitly or explicitly, risks redefining governance as an extension of personal networks rather than constitutional structures.

The public reaction to the ongoing developments is therefore neither excessive nor intrusive. It is an expression of democratic vigilance. Citizens are not demanding internal party secrets; they are seeking clarity about the forces shaping public administration. That distinction matters. Curiosity about governance is not dissent; it is participation.

There is also a moral dimension to the issue. Public trust is not sustained by power alone; it is sustained by candor. Leaders who speak plainly about their decisions strengthen institutions even when those decisions are contested. Leaders who rely on cryptic affirmations weaken confidence even when their intentions are defensible. Clarity is not a risk in governance; ambiguity is.

If an agreement exists that influences appointments, policy direction, or administrative structure, then democratic responsibility requires explanation. If no such binding arrangement determines the course of governance, then an unequivocal statement to that effect would restore confidence. What is untenable is the continuation of a political environment in which decisions of public consequence are accompanied by phrases that illuminate nothing.

The deeper concern is not about a single political episode but about precedent. If governance shaped by undisclosed understanding becomes normalized, future administrations may operate under similar expectations. Electoral mandates would gradually lose substantive meaning, replaced by informal obligations invisible to the electorate. That trajectory would not represent democratic evolution; it would represent democratic erosion.

Power in a democracy is not self-justifying. It is justified through accountability, transparency, and responsiveness to the public will. The people are not spectators to governance; they are its source. To govern without explaining the framework within which decisions are made is to invert that relationship.

The situation in Rivers State therefore presents an opportunity as much as it presents a challenge. It is an opportunity for those in authority to reaffirm a foundational democratic principle: that public office is exercised openly, in trust, and with respect for the people’s right to know. It is an opportunity to replace speculation with clarity and suspicion with confidence.

Ultimately, the question that echoes across the state and beyond is neither rhetorical nor adversarial. It is democratic at its core. If an agreement shapes governance, what are its terms, its limits, and its implications for public authority? And if governance is truly independent, why should transparency be feared?

Citizens did not vote for coded messages. They voted for accountable leadership. In a democracy, legitimacy does not flow from declarations of agreement; it flows from the consent of an informed people. Without that consent, power may endure, but trust does not.