Africa

Kemi Badenoch: Legally Wrong, Culturally Right – Unpacking Nigeria’s Gender Divide -By John Egbeazien Oshodi

The Nigerian Constitution, in its letter, promotes gender equality. Section 25(1)(a) affirms that any person born in Nigeria to a Nigerian parent—mother or father—is a citizen by birth. There is no ambiguity in this clause. Yet, legal clarity does not always translate into public consciousness or bureaucratic behavior. Badenoch’s claim, though inaccurate in law, inadvertently reveals a deeper disconnection between law and life: how institutional and cultural practice can render even the most unambiguous constitutional rights uncertain in the public mind.

A recent statement by Kemi Badenoch, the British Conservative Party leader and a woman of Nigerian descent, sparked a storm of public introspection. Speaking on her inability to transmit Nigerian citizenship to her children because she is a woman, Badenoch’s claim was factually incorrect. Nigeria’s Constitution—specifically Chapter III, Section 25—clearly permits either parent to pass citizenship by birth. And yet, her statement struck a raw nerve across the country. Why? Because although she erred in law, she may have spoken an uncomfortable emotional and cultural truth—one that Nigerian women know too well

For millions of Nigerian women, the Constitution’s gender neutrality is not mirrored in daily life. It is diluted by custom, weakened by tradition, and often rendered void by institutions that operate under deeply patriarchal assumptions. Badenoch, perhaps unwittingly, exposed a larger truth: that legal texts often serve as hollow instruments when society is built on unwritten rules that silently override them. In Nigeria, the law may declare women equal—but culture too often replies, “Not quite.”

The Constitution Speaks: Legal Equality on Paper

The Nigerian Constitution, in its letter, promotes gender equality. Section 25(1)(a) affirms that any person born in Nigeria to a Nigerian parent—mother or father—is a citizen by birth. There is no ambiguity in this clause. Yet, legal clarity does not always translate into public consciousness or bureaucratic behavior. Badenoch’s claim, though inaccurate in law, inadvertently reveals a deeper disconnection between law and life: how institutional and cultural practice can render even the most unambiguous constitutional rights uncertain in the public mind.

The Unwritten Code: Cultural Realities of “Second-Class” Status

Despite constitutional guarantees, Nigerian women are too often bound by cultural codes that treat them as auxiliaries to men—appendages to lineage, not inheritors of it; bearers of children, not architects of legacy. These codes are rarely written down, yet they are enforced with rigorous consistency in families, religious spaces, and political institutions. Women are routinely taught to serve before they speak, to belong to someone before they belong to themselves. In this invisible architecture of tradition, being female means navigating a society that offers formal equality but informal erasure.

The “Doctor (Mrs.)” Syndrome: How Titles Reveal Social Hierarchy

In professional settings, many accomplished Nigerian women list their names as “Dr. (Mrs.)” or “Barr. (Mrs.),” a hybridization that reveals something deeper than courtesy—it exposes the societal pressure to append marital status to professional worth. For male professionals, their identity stands alone. For women, it is often made to stand beside or beneath that of a husband. This titling is not benign; it conditions public perception and subtly affirms that even at the height of her achievements, a woman is expected to remain tethered to a man’s identity. It is a psychological code—a cultural watermark—signaling that women cannot be whole without male anchorage.

Male Primogeniture: The Inheritance of Inequality

In many Nigerian families—especially across southeastern and midwestern regions—ancestral inheritance remains a male entitlement. Land, lineage, and legacy often pass from father to son, while daughters are quietly excluded. A woman, no matter how devoted to her family or how present she was in its growth, is often treated as a temporary member of her birth home—someone destined to “marry out” and therefore unfit to inherit what symbolizes continuity.

This practice isn’t always written down, but it is lived with unyielding consistency. The ancestral home becomes a symbol not just of heritage, but of hierarchy—a space where sons are successors and daughters, despite shared blood, are outsiders. Even when women wish to speak up, cultural pressure, emotional guilt, and fear of communal shame often silence them. Many are told not to disrupt the family peace, not to challenge their brothers, not to “fight over land.”

Inheritance in such contexts is not merely about property; it is about who is seen as central to the family story and who is written into its future. In Nigeria, that future is still most often drawn in the male voice. For daughters, it becomes another silent loss—of roots, of recognition, and of rightful place.

Polygyny vs. Polyandry: Unequal Rights to Intimacy

Polygyny remains socially and legally accepted in Nigeria under customary and Islamic law. A man may have multiple wives, and his authority is rarely questioned. Polyandry, on the other hand, is not only illegal but unthinkable in most Nigerian communities. This asymmetry reveals a deeper cultural logic: that men possess women, while women are not expected to possess men. Female sexuality is to be controlled; male sexuality is to be accommodated. The institution of marriage, under this arrangement, reinforces patriarchal power—one where a woman’s emotional and physical autonomy is subsumed beneath a man’s desire and entitlement.

Gender Segregation in Sacred and Public Spaces

In churches, mosques, shrines, and traditional festivals, women are often placed behind curtains, seated in separate rows, or excluded from sacred rituals. These divisions are not merely spatial—they are symbolic. They signal that female presence is secondary, potentially contaminating, or too provocative for shared spaces of power and holiness. In many communities, even political gatherings mimic this separation, keeping women at the periphery of decision-making. When a society repeatedly separates women from the front, it begins to see them as spectators, not participants—present, but powerless.

Power Eludes Her: Political Underrepresentation as National Norm

Nigeria’s political landscape remains astonishingly male. The 10th National Assembly counts just four women out of 109 Senators—barely 4%. No woman has ever been elected President. This democratic exclusion is not accidental. It is the product of financial gatekeeping, gendered violence, party politics hostile to women, and a cultural mindset that sees leadership as an inherently male domain. Women in politics are often ridiculed, hypersexualized, or dismissed as mere token figures. The result is a political system that, while formally open, is functionally closed to half the population.

Institutional Discrimination: Policing Women’s Bodies and Choices

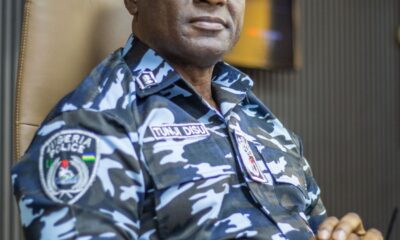

Historically, the Nigeria Police Force enforced rules requiring female officers to seek permission before marrying and subjected their prospective husbands to character checks. Pregnant but unmarried female officers faced dismissal—punishments never applied to their male colleagues. Though court rulings have recently deemed such policies unconstitutional, they existed for decades, shaping careers and crushing dignity. These policies did not merely regulate behavior; they institutionalized the idea that women in uniform are subjects to be controlled, not professionals to be trusted. Even when repealed, the emotional residue of such rules lingers in organizational culture.

Denial of Bodily Autonomy and Justice: Sexual Violence and Marital Rape

This is perhaps the clearest example of how deeply the law and culture collude to deny women full humanity. When Nigerian women are raped or sexually assaulted—especially within marriage—the state often looks away. Under many interpretations of the Penal and Criminal Codes, a husband cannot rape his wife. The very idea is denied legal standing, rooted in the colonial assumption that marriage entails perpetual consent. Although the Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act of 2015 criminalizes marital rape, it has not been uniformly adopted across Nigeria’s states.

Even outside marriage, survivors face uphill battles: police skepticism, cultural shame, weak prosecution, and minimal psychological support. Justice is not just delayed—it is delegitimized. Women are told their pain is private, their suffering normal, their silence preferable. In this system, the body of a woman is not her own—it is a negotiated territory between family honor, male desire, and judicial apathy.

Conclusion: A Legally Wrong Statement, A Psychologically Right Reality

Kemi Badenoch’s claim—that she could not pass Nigerian citizenship to her children because she is a woman—was legally incorrect. But to dismiss her entirely on that basis is to miss a deeper truth: her words echoed the silent, daily experience of millions of Nigerian women and girls who are legally equal, yet culturally subordinated.

Her misstatement captured something the law cannot fully explain: that being a woman in Nigeria often means navigating life as a second-class citizen—not on paper, but in practice. It means living in a society where tradition polices your body, where religion segregates your voice, where politics erases your presence, and where marriage sometimes suspends your right to consent.

Even for the women who rise—into the judiciary, into the Senate, into the boardrooms of Nigeria’s largest corporations—there is a ceiling made not just of glass, but of scrutiny and suspicion. She may be addressed as “Justice,” “Minister,” or “Madam Director-General,” but she must be careful—careful not to be too visible, too vocal, too forceful. For if she speaks too directly, she is labeled arrogant; if she pushes too hard, she is seen as disruptive; if she succeeds too freely, whispers of impropriety follow. Power is granted, but only on condition of restraint.

Now, in her own voice and with striking finality, Badenoch has made her inner break with Nigeria clear. In a new interview, she declared: “I don’t identify with it [Nigeria] anymore.” She has not renewed her Nigerian passport in decades. She had to apply for a visa to bury her own father. She remembers how her parents—disillusioned and despairing—once told her, “There is no future for you in this country.”

For many Nigerian women, this isn’t just her story—it is their story in waiting. A slow psychic divorce from a nation that claims them but does not protect them. A country that names them citizens but renders them culturally expendable. The ache of belonging to a homeland that refuses to belong to them.

This is not merely a legal failure. It is a psychological wound—one that teaches women to internalize inferiority. It is a social structure that punishes assertiveness in women while rewarding control in men. And it is a cultural contradiction that praises women publicly as “nation builders,” yet limits their power privately through norms, inheritance, and silence.

As Nigeria moves further into the 21st century, it must confront the emotional, legal, and spiritual cost of this imbalance. Justice must reach into the marrow of national identity. Equality must mean more than citizenship—it must mean inclusion, visibility, autonomy, and care.

And in that sense, Badenoch’s flawed comment and final renunciation did what the Constitution alone has not yet achieved: they forced Nigeria to look inward and ask a harder question—if a woman must leave to feel whole, what kind of nation has she truly left behind?

Psychologist John Egbeazien Oshodi

Professor John Egbeazien Oshodi is an American psychologist, educator, and author specializing in forensic, legal, clinical, and cross-cultural psychology, with expertise in police and prison science, juvenile justice, and family dependency systems. Born in Uromi, Edo State, Nigeria, and the son of a 37-year veteran of the Nigeria Police Force, his early immersion in law enforcement laid the foundation for a lifelong commitment to justice, institutional transformation, and psychological empowerment.

In 2011, he introduced state-of-the-art forensic psychology to Nigeria through the National Universities Commission and Nasarawa State University, where he served as Associate Professor of Psychology. Over the decades, he has taught at Florida Memorial University, Florida International University, Broward College (as Assistant Professor and Interim Associate Dean), Nova Southeastern University, and Lynn University. He currently teaches at Walden University and holds virtual academic roles with Weldios University and ISCOM University.

In the U.S., Prof. Oshodi serves as a government consultant in forensic-clinical psychology and leads professional and research initiatives through the Oshodi Foundation, the Center for Psychological and Forensic Services. He is the originator of Psychoafricalysis, a culturally anchored psychological model that integrates African sociocultural realities, historical memory, and symbolic-spiritual consciousness—offering a transformative alternative to dominant Western psychological paradigms.

A proud Black Republican, Professor Oshodi is a strong advocate for ethical leadership, institutional accountability, and renewed bonds between Africa and its global diaspora—working across borders to inspire psychological resilience, systemic reform, and forward-looking public dialogue.