Africa

Nigeria Destabilizing As A Key Regional Actor. Interview with Professor Sergiu Mișcoiu -By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh

Second, the evolving multipolar economic and political architecture (greater Chinese, Gulf, and assertive Russian engagement) offers African states alternative partners—reducing Western leverage and complicating coordinated responses to governance problems. African governments may exploit great-power competition to seek favorable terms or diplomatic cover. Analysts note that this makes consistent international pressure harder to sustain.

Nigeria, with an estimated population of 220 million and largely considered as West African economic giant, was designated as a “Country of Particular Concern” due to persistent Christian-Moslem conflicts, often resulting in abduction and massive deaths. The alleged ‘genocide’ accusation made by U.S. President Donald Trump based on several reports monitored down the years. Trump further threatened to cut aid and undertake a serious military action. In 2020, Nigeria was first labeled as such, and there has been new dimensions with emergence of terror groups and intensifying ethnic-religious disputes mostly in the northern part of the country.

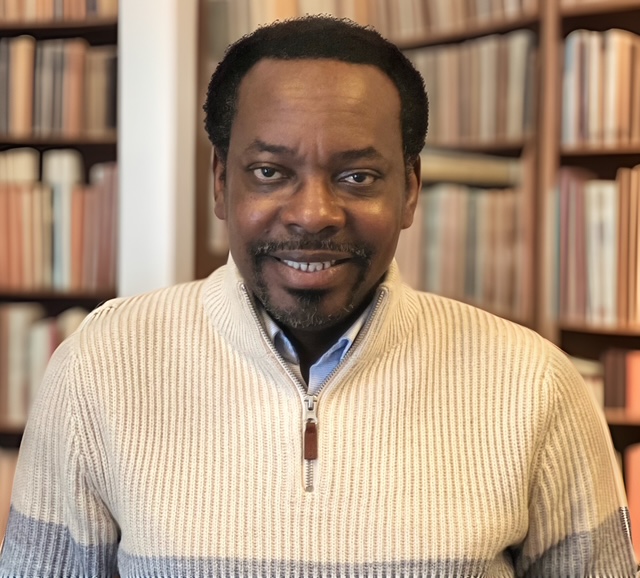

In this interview conversation, Professor Sergiu Mișcoiu at the Faculty of European Studies, Babes-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca (Romania), where he also serves as a Director of the Centre for International Cooperation and as Director of the Centre for African Studies, discusses aspects of the ethnic-religious crisis, as well as system of governance, human-rights violations and corruption in Nigeria. He also offers, within the context of changing global order, solution-strategies and other systemic measures for the continential organization, the African Union (AU). Below are the interview excerpts:

Would you agree with President Trump’s designation of Nigeria as a Country of Particular Concern (CPC) over alleged massive attacks on Christians? Is that an explicit genocide?

Professor Sergiu Mișcoiu: The U.S. CPC label is a statutory tool under the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) that targets states that engage in or tolerate particularly severe violations of religious freedom (systematic, ongoing, egregious acts such as killings, disappearances or torture). The U.S. State Departments 2024—25 reporting and recent press coverage show the United States re-designated Nigeria as a CPC on October 31, 2025 amid renewed concern about persistent religiously-tinged violencce.

Whether the violence amounts to genocide is a distinct legal question. Genocide under the 1948 Genocide Convention requires not only prohibited acts (killings, causing serious harm, deliberately inflicting life-destroying conditions, etc.) but specific intent to destroy, in whole or part, a protected group (national, ethnical, racial or religious). That intent element is legally demanding and must be proven. The CPC designation signals severe religious-freedom violations but is not the same as a judicial finding of genocide. Independent experts and governments typically look for patterns of intent and state or organizational policy before using the genocide label.

In short: the CPC designation is a credible diplomatic response to documented, serious attacks on religious communities. It does not, by itself, equate to a legal determination of genocide—such a finding would require rigorous, independent investigation of intent and patterns of conduct. For policy and moral rhetoric, however, CPC status elevates international scrutiny and possible targeted measures.

How would you argue that Nigeria is increasingly facing serious challenges with governance, ethnic/religious intolerance, frequent abductions and killings?

Professor Mișcoiu: A reasoned argument links observable security and governance indicators, official reporting, and scholarship. First, Nigerian security trends: States Department and independent human-rights reports document widespread abuses—arbitrary killings, kidnappings, communal massacres, and repeated attacks by Boko Haram/ISWAP in the northeast, banditry and cattle-farmer violence in central states, and separatist or criminal violence in the south. These trends create diffuse insecurity that disproportionately harms civilians.

Second, governance deficits compound insecurity. Chronic corruption, weak accountability, uneven rule-of-law capacity, and politicized security forces reduce the state’s ability to protect citizens or to deliver services—factors underlined in CRS and Amnesty reporting and frequently cited by analysts. Where governance is weak, non-state armed groups and criminal networks exploit grievances and impunity.

Third, identity politics and resource pressures intensify intolerance. Competition over land, grazing, and local power has been racialized and religiously framed in many attacks; opportunistic militants sometimes target communities along ethno-religious lines, producing cycles of communal reprisal. Kidnapping for ransom has become a lucrative business model, increasing abductions across regions.

Finally, these are mutually reinforcing — insecurity erodes governance capacity and legitimacy, while poor governance prevents effective, rights-respecting responses. Any policy response must therefore combines security, anti-corruption, rule-of-law reforms, and community reconciliation, rather than military fixes alone.

Do Britain, Canada and other global powers share the U.S. position, citing corruption, misappropriation and lack of accountability in Nigeria?

Professor Mișcoiu: Several Western governments and international bodies have for years raised concerns about governance, human-rights violations and corruption in Nigeria. The UK has publicly urged investigations into human-rights abuses during Universal Periodic Review engagements and other fora; Canada and other partners have regularly criticized corruption and inadequate accountability. These are long-standing, cross-cutting criticisms rather than an identical, unified CPC framing.

However, governments differ in emphasis and tactics. Some focus on human-rights reporting and targeted sanctions; others prioritize development, anti-corruption assistance, or security cooperation. After the U.S. CPC move (Oct 2025), several partners expressed concern about violence against civilians but some—like Abuja—rejected the characterization as based on faulty information. Media and policy analysis note EU, UK and Commonwealth diplomatic pressures over governance and accountability, but not always with identical legal designations or calls for punitive action.

Transparency International, NGO reports and CRS briefings also document decades-long corruption, money-laundering allegations and weak accountability mechanisms in Nigeria—facts that inform Western governments rhetoric. Yet geopolitical calculations (security, trade, regional stability) mean powers often calibrate responses to avoid destabilizing a key regional actor. In sum: there is overlapping concern about corruption and governance, but differences in policy instruments and public framing remain.

U.S. and Africa: comparative assessment of Obama, Biden, and Trump policies toward Africa — and has Washington interfered in Nigerias internal affairs?

Professor Mișcoiu: Broad comparative sketch: Obama pursued engagement framed by development, health diplomacy (PEPFAR, Power Africa), multilateralism and some security cooperation, while often criticized for limited strategic follow-through. Biden articulated a 2022 Africa strategy emphasizing partnerships, economique development and multilateral cooperation (U.S.—Africa Leaders Summit, food-security initiatives). Trump’s approach was more transactional and selective: an emphasis on security cooperation at times, trade deals, and—especially during his 2017—2020 term—reticence or confrontational rhetoric; the 2025 re-designation of Nigeria as CPC reflects a Trump presidency more willing to use moral-legal instruments for political audiences.

Scholarly reviews and policy centers (CSIS, CFR) trace these continuities and divergences.

On interference: diplomacy often includes public criticism, designations, sanctions and conditionality; these tools are within sovereign states’ foreign-policy toolkits. The CPC designation and public threats of punitive measures or even military options (as publicly invoked by President Trump) are politically sensitive and can be read as intrusive by the target state. Nigeria’s government has explicitly rejected the CPC labeling and framed the security problem as terrorism rather than state-sponsored religious persecution—arguing that U.S. moves risk infringing sovereignty and misdiagnosing drivers of conflict. Whether this rises to unlawful interference depends on definitions: diplomatic pressure and sanctions are legal instruments of foreign policy; unilateral military action without consent would be a far stronger form of interference.

Implications for other African countries and the changing role of the African Union (AU) amid emerging global architectures?

Professor Mișcoiu: Implications are threefold. First, external designation/sanction regimes increase reputational and aid-conditional risks for states that fail to address rights and governance deficits; other African governments may face similar scrutiny over religious-freedom, human-rights or corruption records. This raises incentives for domestic reform but also risks defensive nationalism and alignment shifts (leaning toward non-Western partners who promise less conditionality).

Second, the evolving multipolar economic and political architecture (greater Chinese, Gulf, and assertive Russian engagement) offers African states alternative partners—reducing Western leverage and complicating coordinated responses to governance problems. African governments may exploit great-power competition to seek favorable terms or diplomatic cover. Analysts note that this makes consistent international pressure harder to sustain.

Third, the AU’s role can deepen: by strengthening continental mechanisms for conflict prevention, human-rights monitoring, and peer accountability (AU human-rights instruments, conflict mediation, and the African Peer Review Mechanism), Africa can reduce external conditionality and assert continental sovereignty. For the AU to be effective it must (a) increase rapid response capacity, (b) offer credible impartial mediation and investigation capacity accepted by member states, and (c) build partnerships that reinforce, not supplant, African agency. Cooperative engagement with the UN and regional economic communities will be essential. In short: designation politics sharpen the need for stronger African institutions that can both hold members to account and defend African agency in a changing global order.

—