Africa

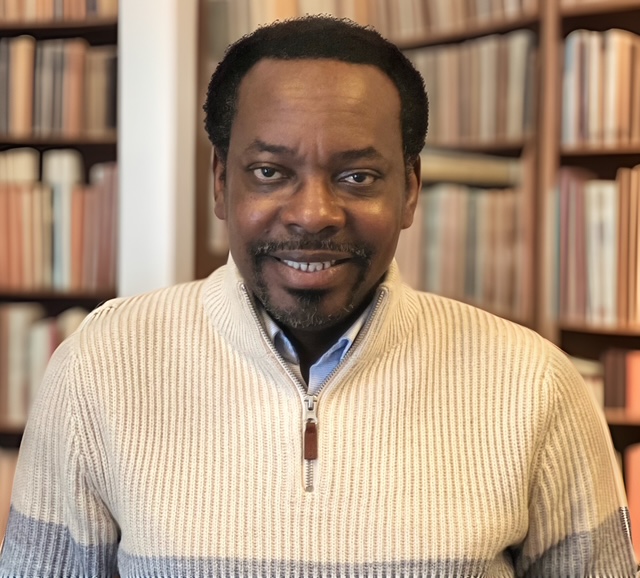

Nigeria’s Silent Emergency: Navigating the Cost-of-Living Tsunami -By Garba idi Garba

Nigeria stands at a crossroads. The cost-of-living tsunami is real, widespread, and demanding more than rhetoric. It requires concerted action, policy courage, and societal empathy. To turn the tide will take more than hope—it will take hard reforms, collective sacrifice and a reimagining of what stability and prosperity mean in today’s Nigeria.

In recent months, Nigerians have found themselves confronting a crisis far quieter than militant attacks or political upheavals—but no less devastating. The cascading impact of inflation, currency depreciation and subsidy removal has created a perfect storm, thrusting millions into a daily struggle just to survive. This isn’t about one sector faltering—it’s about the foundations of everyday life cracking under pressure.

At the heart of the matter is the surge in food and transportation costs. Staple goods like rice, beans and yam have more than doubled in price in many parts of the country, as the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reports a food inflation rate beyond 30 per cent. With the removal of longstanding fuel subsidies and the liberalisation of the naira, what were incremental increases have become seismic shifts in cost. The price of petrol has spiked, public transport fares have surged, and the increase ripples outward: manufacturers pass on higher freight costs, shopkeepers raise mark-ups, and a large slice of the Nigerian population—especially low-income earners—is squeezed tighter than ever.

The domestic currency’s devaluation has intensified the pain. Because Nigeria depends heavily on imports—whether processed food items, raw materials or consumer goods—a weaker naira means more naira must be spent for the same volume. The government’s policy shift toward market-determined exchange rates was hailed for its long-term logic but the short-term effect has landed hardest on ordinary households. The remarkable irony is that even as Nigeria boasts Africa’s largest population and one of its largest economies, the purchasing power of many Nigerians has plummeted.

This economic squeeze has powerful social consequences. People are eating fewer meals, skipping medical check-ups, postponing school fees and struggling to afford the barest essentials. Small and medium enterprises, once seen as engines of growth, are faltering as customers shrink and operating costs soar. Unprecedented living costs are fuelling social restlessness: protests, strikes, and growing discontent are no longer fringe but symptomatic of a wider malaise. The recently-reported general strikes and labour calls across the states underscore that many Nigerians feel the system is failing them.

Yet, amid this crisis, some hopeful signs have emerged. The Central Bank of Nigeria Governor recently noted that inflation might be showing early signs of slowing, pointing to modest improvements in the foreign-exchange market and some moderation in petrol prices. But for millions of Nigerians, these glimmers remain distant: the lived reality remains one of escalating hardship, not relief.

What does this mean for policy and hope in Nigeria? First, any durable solution must go beyond short-term bandaids. Wage policies, social safety nets and targeted subsidies must reflect the new cost-baseline of Nigerian life. It is no longer adequate to benchmark on old incomes when prices have moved so rapidly. Second, the diversity of Nigeria’s economy—its agriculture, manufacturing, services—must be leveraged to mitigate import dependency. Strengthening domestic production means insulating households from global currency shocks and supply-chain tremors. Third, communication and trust matter. If citizens believe reforms are simply about price hikes, the path to structural change becomes politically fraught. Transparent dialogue, phase-in measures and inclusive reforms are essential to avoid societal fracture.

From a human angle, perhaps the most tragic element is that this crisis is neither sudden nor unanticipated. Experts have repeatedly warned that weak job creation, heavy import dependence, and inflationary pressures were chronic vulnerabilities in Nigeria’s system. Yet the convergence of multiple shocks—fuel subsidy removal, naira liberalisation, global inflation—in a short span has brought the system to a near-breaking point. The deeper question now is: will Nigeria learn from this crisis and build resilience, or will cycles of hardship simply repeat?

For the average Nigerian family juggling incomes and outgoings, this moment is urgent. Political timetables and macro-economic indicators can feel abstract when what matters is whether there’s enough money left for food, whether the bus fare goes up again, whether the child’s school fees will be late. The policy levers are in motion, but the measure of success will be whether Nigerians regain the sense that their lives are improving—not merely surviving.

In short, Nigeria stands at a crossroads. The cost-of-living tsunami is real, widespread, and demanding more than rhetoric. It requires concerted action, policy courage, and societal empathy. To turn the tide will take more than hope—it will take hard reforms, collective sacrifice and a reimagining of what stability and prosperity mean in today’s Nigeria.

Garba idi Garba, student of mass communication Kashim Ibrahim University, Maiduguri