Africa

Recalled Ghanaian High Commissioner: Lesson From Ghana For Nigeria -By Isaac Asabor

If Nigeria is to strengthen its democratic fabric, it must embrace a culture where public service is inseparable from public accountability. That transformation begins with a simple but profound shift, from rewarding controversy to rewarding integrity. Ghana has shown that such a shift is possible. The responsibility now rests with Nigeria to decide whether the lesson will be learned or merely observed.

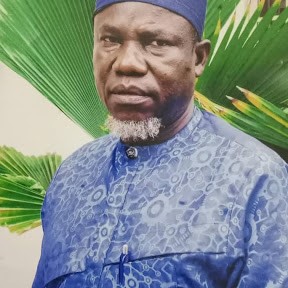

Ghana’s decision to recall its High Commissioner to Nigeria, Baba Ahmed, over alleged involvement in electoral malpractice is more than a diplomatic footnote. It is a statement about the value a country places on public integrity. Acting on allegations of voter inducement during parliamentary primaries in the Ayawaso East Constituency, President John Mahama ordered Ahmed’s immediate recall to preserve the credibility of public office and avoid any perception of impropriety. The action was not predicated on a final judicial verdict. It was grounded in a principle: when public trust is at stake, leadership must act swiftly and decisively.

For Nigeria, the episode presents a stark contrast and a sobering mirror. Where Ghana has opted for precautionary accountability, Nigeria has too often normalized the opposite, reward without resolution, elevation without exoneration, and rehabilitation without responsibility. The difference is not merely procedural; it is philosophical. It is the difference between a state that guards the sanctity of public office and one that frequently treats it as a bargaining chip in political arithmetic.

The Ghanaian government’s reasoning was clear. The Presidency emphasized that Ahmed’s continued stay in office was no longer tenable under the standards expected of public officers, especially as investigations were underway. In other words, the threshold for action was not guilt proven beyond reasonable doubt; it was the preservation of institutional integrity. This is the essence of responsible governance: the recognition that the legitimacy of public institutions depends as much on perception as on proof. When the office is bigger than the occupant, swift action becomes a duty, not a choice.

Nigeria’s recent history tells a different story. In the country’s political culture, controversy has too often functioned as a stepping stone rather than a stumbling block. Individuals whose public records are clouded by allegations of corruption or misconduct frequently resurface in prominent appointments. Instead of facing decisive consequences, many are pacified, rehabilitated, or repositioned. The message transmitted to the public is unambiguous: accountability is negotiable; loyalty is currency.

Consider the recurring pattern in which individuals facing serious questions about their stewardship of public resources are later cleared to contest elections or handed sensitive responsibilities. Investigations linger without closure, and in the vacuum created by delayed justice, political expediency thrives. Institutions tasked with enforcement appear to oscillate between vigor and inertia, depending on the political temperature of the moment. The result is a chronic erosion of public confidence.

Nigeria’s experience with militancy in the Niger Delta offers another instructive example. While the amnesty program brought a measure of stability to a volatile region, it also reinforced a troubling precedent: that disruptive behavior could be rewarded with scholarships and incentives. Peace was purchased, but at a cost, the subtle institutionalization of grievance as leverage. When conflict becomes a pathway to privilege, the line between reconciliation and incentivization blurs. This pattern is further complicated by a national climate in which bandits and terrorist actors are sometimes engaged in negotiation even after carrying out widespread, devastating attacks across the country, particularly in Nigeria’s central region, raising difficult questions about deterrence, justice, and the long-term consequences of bargaining with violence. As Ecclesiastes 8:11 cautions, “Because the sentence against an evil work is not executed speedily, therefore the heart of the sons of men is fully set in them to do evil,” a warning that delayed accountability can embolden further wrongdoing.

The same dynamic is visible in the political sphere. Individuals suspected of misappropriating public funds sometimes find themselves not ostracized but accommodated. Instead of a consistent doctrine of consequences, Nigeria has often operated a doctrine of convenience. Offices are used as instruments of appeasement, and appointments become tools for managing dissent rather than vehicles for service delivery.

Ghana’s action disrupts this logic. By recalling a serving envoy over allegations tied to internal party primaries, the Ghanaian leadership signaled that public office is inseparable from personal conduct, whether at home or abroad. It also reinforced the idea that diplomatic representation is a privilege contingent on unimpeachable standards. The recall was not a declaration of guilt; it was a declaration of values.

The lesson for Nigeria is neither abstract nor unattainable. Accountability does not require perfection. It requires consistency. It requires the willingness to prioritize institutional credibility over political convenience. It requires a clear message that public office is not a sanctuary from scrutiny but a platform for higher standards.

One of the most damaging consequences of Nigeria’s approach to misconduct is the corrosion of deterrence. When consequences are uncertain or absent, the incentive structure tilts toward risk-taking. Public officials operate in an environment where the probability of punishment is low and the potential rewards are high. This imbalance breeds impunity. It transforms governance into a contest of survival rather than a commitment to service.

Ghana’s example demonstrates that decisive action can coexist with due process. The recall of an official pending investigation does not preclude a fair hearing. It simply ensures that the integrity of the office is not compromised while facts are being established. This distinction is crucial. Accountability is not vengeance; it is stewardship.

Nigeria’s institutions, the executive, legislature, judiciary, and anti-corruption agencies, are often described as robust in form but inconsistent in function. Laws exist, codes of conduct are articulated, and oversight mechanisms are established. Yet enforcement frequently falters at the intersection of politics and principle. The challenge is not the absence of rules but the unevenness of their application.

There is also a broader cultural dimension. When the public becomes accustomed to seeing alleged offenders rewarded, cynicism takes root. Citizens begin to doubt the possibility of reform. Trust in governance declines, voter participation weaken, and the social contract frays. Accountability is not merely an administrative practice; it is a moral signal that the state respects its citizens enough to hold power answerable.

Ghana’s recall decision underscores another vital point: leadership is demonstrated not only by grand reforms but by everyday choices that uphold standards. By acting promptly, the Ghanaian presidency affirmed that the reputation of public institutions cannot be mortgaged to individual ambition. The symbolism of the decision is as powerful as its substance. It communicates that public service is conditional on public trust.

Nigeria stands at a crossroads where similar choices are possible. The country’s democratic journey has been marked by resilience and promise, but it remains burdened by a recurring deficit of consequences. Reform does not begin with new rhetoric; it begins with new habits of enforcement. It begins when allegations trigger transparent processes and when officeholders understand that scrutiny is an occupational reality, not an inconvenience to be negotiated.

There are practical steps Nigeria can draw from Ghana’s example. First, establish a consistent protocol that public officials facing credible allegations step aside pending investigation. Second, strengthen the independence of oversight institutions so that their actions are not perceived as politically selective. Third, cultivate a political culture in which appointments are based on merit and integrity rather than strategic appeasement. Finally, reinforce civic education to ensure that citizens demand accountability not as a favor but as a right.

None of these measures is revolutionary. They are, in fact, the basic architecture of responsible governance. What is required is not invention but implementation. Nigeria does not lack capable individuals or sound laws; it lacks a sustained commitment to applying them impartially.

The recall of Ghana’s High Commissioner is a reminder that nations define themselves by the standards they enforce. Integrity is not proclaimed; it is practiced. Public trust is not demanded; it is earned. Where consequences are consistent, confidence grows. Where accountability is selective, skepticism prevails.

Nigeria’s future need not be tethered to its past patterns. The country possesses the institutional framework and human capital to recalibrate its approach to public responsibility. The question is whether it will choose to do so. Ghana has offered a practical demonstration of how leadership can act decisively in defense of public trust. The lesson is clear: the dignity of public office must never be subordinated to the convenience of politics.

If Nigeria is to strengthen its democratic fabric, it must embrace a culture where public service is inseparable from public accountability. That transformation begins with a simple but profound shift, from rewarding controversy to rewarding integrity. Ghana has shown that such a shift is possible. The responsibility now rests with Nigeria to decide whether the lesson will be learned or merely observed.