Africa

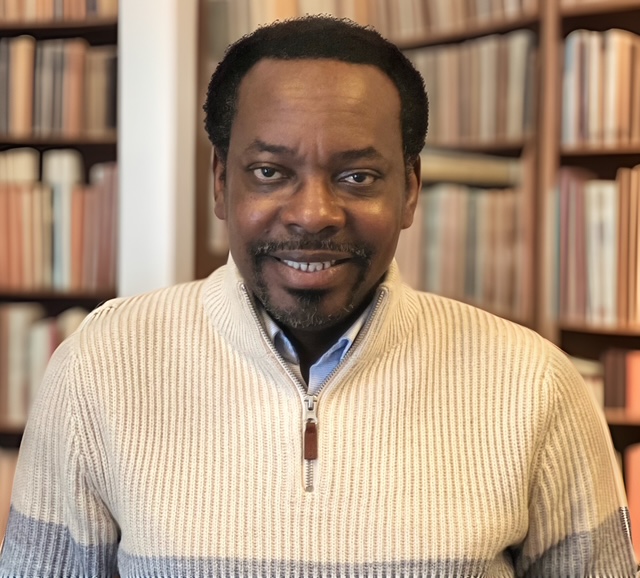

The Biafran Question: Beyond Nnamdi Kanu’s Detention -By Damian Ugwu

The attention of our national discourse must shift from debates about individual actors to the systemic issues that produce them. Until we constructively address those issues, the Biafran question will remain an open wound—painful, unhealed, and threatening to the health of the entire body politic.

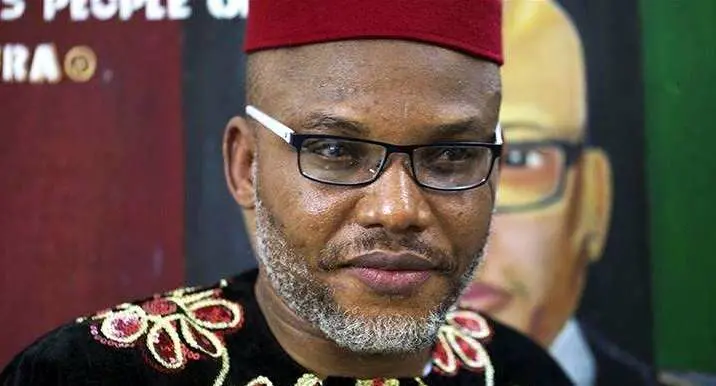

When the debate about Nnamdi Kanu’s continued detention resurfaces, as it inevitably does,I find myself reflecting on a conversation that is simultaneously urgent and unfinished. The leader of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) has become a lightning rod in Nigerian discourse. To some, his release represents the key to restoring peace in a violence-wracked Southeast; to others, he must answer for the atrocities allegedly committed by his Eastern Security Network (ESN) militants since their establishment.

My candid opinion is that both camps miss the fundamental point. The question is not simply what to do with Nnamdi Kanu. The question is why Nigeria continues to produce figures like Nnamdi Kanu.

But first, the background. The contemporary Biafran agitation did not begin with Kanu. In 1999, a young lawyer named Ralph Uwazurike founded the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB), a secessionist organization advocating for an independent Biafran state through stated commitment to non-violent resistance. Within months, the movement attracted hundreds of thousands, mostly young artisans, students, and the unemployed from the Igbo-speaking areas who felt marginalized by Nigeria’s economic and political structures. Their grievances were rooted in historical trauma, contemporary exclusion, and what many saw as the unfinished business of reconciliation from a civil war that ended in 1970 but whose wounds never fully healed.

When Kanu emerged years later with IPOB and its more militant posture, he was not creating something new. He was channeling something old, unresolved, and festering.

The trajectory of this escalation tells its own story. The Obasanjo administration’s immediate response to MASSOB was a military-style clampdown. Between 1999 and 2010, Uwazurike and his followers were subjected to various forms of persecution, arbitrary detention, torture, and extrajudicial killings. In August 2001, for instance, Uwazurike was charged with treason alongside 280 of his members. The absurdity of the government’s heavy-handedness was perhaps best illustrated in September 2004, when 53 MASSOB members and supporters, including two women, were charged for treason after they were arrested in the Abule-Ado suburb of Lagos while participating in a football tournament named the “Ralph Uwazurike Cup”.One struggles to imagine what national security threat was posed by a football match.

By 2006, tired of constant intimidation and the extrajudicial killing of members, some MASSOB supporters began advocating for armed resistance. Uwazurike apparently opposed this, but the momentum had shifted beyond one man’s control. More radical groups emerged: Biafra-Must-Be (BIAMUS), Biafra Commandos, and the Biafra Resistance Army. Benjamin Onwuka’s Biafra Zionist Front(BZF) went further still. On 8 March 2014, his group attacked and seized the Enugu State Government House, taking control of both the building and the state broadcasting station for approximately four hours and hoisting the Biafran flag at the entrance. Onwuka subsequently issued an ultimatum to non-Igbos living in “Biafran territory” to vacate by 31 March 2014 or face a bloodbath. Onwuka and his group were rounded up and currently serving terms in prison.

This is the context in which Nnamdi Kanu rose to prominence; not as the originator of Biafran agitation, but as the beneficiary of a government strategy that consistently chose confrontation over conversation, suppression over dialogue. Each crackdown radicalized a new cohort. Each arrested football tournament produced more militants than it detained.

To understand what might bring lasting peace to the Southeast, and by extension, strengthen Nigeria’s fragile union, we must first acknowledge the layered nature of this conflict. The current agitation is fueled by a combustible mix: perceived political marginalization of the Igbo people, economic underdevelopment despite the region’s resources, systematic exclusion from federal appointments and infrastructure projects, and heavy-handed security responses that have escalated rather than de-escalated tensions. The sit-at-home orders, violent clashes, and attacks on security forces have created a climate of fear and economic paralysis that serves no one’s interests.

The government’s approach; proscribing IPOB as a terrorist organization and relying primarily on military operations, has not resolved the underlying issues. If anything, it has intensified them. What Nigeria needs is not another security “victory” but the political courage to pursue difficult reforms that sustainable peace demands.

This requires, first, genuine political dialogue. Not the performative kind where government officials lecture aggrieved communities about patriotism, but inclusive conversations that bring together federal representatives, southeastern governors, traditional rulers, religious leaders, civil society organizations, and yes, even those advocating for Biafran independence, politically sensitive though that may be. South Africa’s CODESA negotiations offer instructive lessons about creating space for seemingly irreconcilable parties to find common ground. The dialogue must allow grievances to be aired without preconditions, even if the ultimate solution falls short of independence.

Second, Nigeria needs a truth and reconciliation process focused on both historical and contemporary wounds. The Nigerian Civil War’s aftermath was marked by a policy of “no victor, no vanquished,” but in practice, many Igbos experienced what felt like systematic exclusion. The abandoned property issues in Port Harcourt and other cities, the currency exchange that impoverished Igbo families overnight, the lack of meaningful reconstruction in the Southeast—these were never properly addressed. More recently, incidents like the 2016 Python Dance military operation and various crackdowns on protesters have deepened the trauma. A carefully designed truth-telling process, perhaps modelled on South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission but adapted to Nigerian realities, could help acknowledge these pains while creating space for healing.

Third, concrete political and economic reforms must demonstrate that engagement yields tangible benefits. This might include restructuring Nigeria’s federal system to allow greater regional autonomy, implementing genuine fiscal federalism so regions benefit more directly from their resources, and ensuring equitable representation in federal institutions and security agencies. The Southeast needs visible infrastructure development, not as a favour, but as redress for decades of comparative neglect. The Second Niger Bridge’s completion is a start, but roads, power, education, and healthcare infrastructure remain inadequate.

Any disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration program must be handled with extreme sensitivity. Unlike conventional rebel groups, many IPOB supporters see themselves as freedom fighters defending their people against oppression. Simply disarming them without addressing their fundamental concerns will fail. Former ESN members need pathways to legitimate livelihoods through skills training and employment programs, but this must happen within a framework where they feel their sacrifices and concerns have been heard.

Security sector reform in the region is equally critical. The perception that federal security forces are an occupying army rather than protectors must change through accountability for past excesses, better training in community policing, recruitment of more personnel from the Southeast, and establishing civilian oversight mechanisms that communities trust.

Economic investment and youth employment programs are urgent. Much of the agitation’s energy comes from unemployed young people who feel they have no stake in Nigeria’s future. Creating genuine opportunities, not just rhetoric, can change their calculations.

Northern Ireland’s peace process offers instructive lessons. It took decades of dialogue, multiple failed attempts, addressing economic disparities, police reform, and ultimately power-sharing arrangements before sustainable peace emerged. Colombia’s peace process with FARC, despite its imperfections, demonstrates how even long-standing insurgencies can be resolved through patient negotiation combined with transitional justice mechanisms.

The challenge, of course, is political will. Peacebuilding requires leadership at the federal level willing to make genuine concessions and address structural inequities. It requires patience when political incentives often favor short-term military “victories.” And it requires those advocating for Biafra to accept that even if full independence isn’t immediately achievable, meaningful autonomy and equity within Nigeria might be.

There are lessons here that mirror my study of neighbouring Sierra Leone, where President Julius Maada Bio reflected on his country’s brutal civil war. Could it have been averted? Bio believes it could have, and I find his reasoning compelling. The inability of political leadership to read the situation correctly in the early stages, the preference for military solutions over political dialogue, the failure to address underlying grievances; all contributed to a humanitarian disaster that killed at least 50,000 people and displaced half the country’s population.

Nigeria faces a similar choice today. The contagious nature of crisis means that instability in one region rarely remains contained. The Biafran question will not resolve itself through Kanu’s continued detention or his release. It will only find resolution when Nigeria’s political leadership has the courage to pursue the difficult reforms that sustainable peace demands, reforms that acknowledge historical wrongs, address contemporary grievances, and offer all Nigerians, regardless of ethnicity, a genuine stake in the country’s future.

The question isn’t just what model can bring peace to the Southeast. It’s whether Nigeria’s leaders are prepared to do what leadership requires: placing the needs of the people above political expediency, having the courage of conviction even when choices are costly, and understanding that elections alone do not constitute democracy. True democracy, as former Vice President Yemi Osinbajo recently reminded an audience, delivers dignity—food on the table, education for children, safety in our streets, and hope for the future.

Until Nigeria addresses the Igbo question at its roots rather than treating its symptoms, we will continue this cycle: detaining one agitator only to watch another emerge, deploying military force that breeds more resentment, and wondering why peace remains elusive in a region that simply wants to feel like equal partners in the Nigerian project.

The attention of our national discourse must shift from debates about individual actors to the systemic issues that produce them. Until we constructively address those issues, the Biafran question will remain an open wound—painful, unhealed, and threatening to the health of the entire body politic.