Africa

Degrees Without Intelligence: Nigeria’s Leadership Crisis in Protection and Poor Judgment -By Prof John Egbeazien Oshodi

For years, Nigerians across every region have demanded the creation of state police. Governors have cried out repeatedly, security experts have insisted on it, traditional rulers have endorsed it, and communities under attack have begged for localized, accountable protection. Yet every Inspector General of Police pushes back, clinging to the centralized structure as though decentralization were a national threat. President Tinubu also appears to be walking the same path — offering soft hints, forming committees, making cautious statements, and delaying any real reform until after elections.

Nigeria is a nation overflowing with certificates. Our leaders carry LLBs, MScs, PhDs, foreign diplomas, fellowships, honorary doctorates, and endless titles. Their offices are decorated with frames that tell a story of long years in classrooms, conferences, and foreign seminars. On paper, this should be the golden age of intelligent governance. Yet the daily reality of Nigerians says something very different: decisions coming from the top often contradict logic, common sense, and basic human empathy. This is why Pastor Paul Enenche’s statement that some leaders “need psychiatric evaluation” resonated so deeply. He was not casually abusing those in office; he was verbalizing a reality that many Nigerians quietly observe — that there is a widening gap between academic credentials and practical intelligence. We see leaders who can recite theories but cannot solve problems, leaders who can read reports but cannot interpret danger, leaders who can speak English elegantly but cannot think clearly when lives are at stake. In such a context, degrees become decorations, not tools. Education becomes a performance, not a source of wisdom. The painful truth is that in Nigeria today, education alone has not produced judgment, insight, or moral courage at the level required for national leadership.

Galadima’s Outcry and the Collapse of Basic Reasoning

Buba Galadima’s condemnation of the closure of 41 unity schools as “shameful” was more than political criticism; it was a diagnosis of collapsed reasoning at the highest levels of government. In any sane society, when schools are under attack, the first question is: how do we protect them? How do we strengthen security, reinforce infrastructure, train personnel, involve communities, and deploy technology to make these places safer? Only in a system where judgment has malfunctioned do leaders decide that the way to protect education is to shut it down. Closing schools because terrorists are targeting them is not policy; it is surrender dressed up as caution. It tells criminals that the state will retreat whenever they advance. It tells parents and children that their learning is negotiable. It tells the world that the government has lost confidence in its own capacity to secure its youngest citizens. Galadima’s choice of the word “shameful” captured the psychological humiliation of this decision. This is exactly the kind of leadership behavior Pastor Enenche was reacting to: decisions that break the most basic principles of governance, trauma care, and child protection, made by people who are supposed to be educated and enlightened. When those in charge cannot see that shutting schools damages the nation’s future more than it protects it, we are no longer dealing with a lack of information; we are dealing with a deficit of thinking.

Tinubu’s VIP Security Withdrawal: A Good Idea Damaged by Poor Judgment

On the surface, President Tinubu’s directive to withdraw police officers from VIP protection looks like an overdue correction. For many years, the Nigerian Police Force has been stretched thin not because there are too few officers, but because too many of them have been captured into private service. Instead of patrolling streets, investigating crimes, securing schools, and protecting communities, officers have been stationed at private homes, government lodges, private parties, and even shopping trips. They open gates, carry handbags, escort children to school, stand behind madams in church, and function as living symbols of status for the elite. This long-standing misuse has gutted public policing capacity. So when Tinubu ordered that these officers be withdrawn and redeployed to core policing, it should have been a turning point. However, the next part of the policy revealed the same pattern of poor judgment that runs through so many Nigerian reforms: instead of directing VIPs to use licensed, armed private security as is done in functional societies, the president’s directive simply shifted the burden to the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps. In other words, instead of using the opportunity to restore a clear separation between public security and private protection, the system chose to replace police servants with Civil Defence servants. The uniform may change, but the distortion remains. This is what happens when leaders grasp the outline of a problem but do not understand the architecture of a solution. The intention to free up police manpower is correct; the choice to fill the gap with another public agency is evidence of incomplete thinking.

The Long History of Empty IGP Promises

For nearly two decades, almost every Inspector General of Police in Nigeria has announced—with confidence and ceremony—that police officers would be withdrawn from VIP protection and returned to public duty. Every new IGP repeats the same pledge. Every year, nothing changes. Officers continue to carry handbags, open gates, run errands, and serve private households while communities remain unsafe. This repetitive cycle is one of the clearest signs of leadership poor judgment in the system: announcements without enforcement, directives without monitoring, policies without courage, and reforms without execution. The fact that each IGP keeps promising the same thing, knowing it will not be implemented, exposes a chronic institutional weakness. Now that President Tinubu has issued the same order, the real test is not the announcement — Nigeria has heard those before — but whether this presidency has the judgment, backbone, and administrative intelligence to enforce what previous police chiefs could not. The policy is only meaningful if it finally breaks the circle of empty promises.

The Difference Between Lawful Off-Duty Detail and Nigerian Abuse of Uniformed Officers

It is important to draw a clear line between legitimate security arrangements and the Nigerian reality. Around the world, and even within Nigeria’s own regulatory framework, there are lawful circumstances where off-duty officers can provide paid security services. A police officer or other uniformed agent may be assigned to guard a bank, escort cash in transit, oversee security at a large event, or temporarily support a business facility facing a high-risk situation. These arrangements are regulated, documented, and defined by clear rules. They are meant to enhance safety in places where public and private interests intersect, and they are part of a wider professional culture of security. What Nigeria has normalized, however, goes far beyond this. We have turned full-time state officers into domestic staff. These are people who were trained with public funds to fight crime and defend the nation, yet they are used to carry handbags, polish shoes, wash cars, open doors, walk dogs, push shopping carts, and act as human scenery for wealthy families. They stand for hours behind individuals whose main interest is personal prestige, not public safety. This is not off-duty detail; it is humiliation in uniform. It degrades the officer, wastes public resources, and leaves communities vulnerable. Above all, it reveals a leadership class that has lost the ability to distinguish between an officer of the state and a private servant. That is not a failure of education; that is a failure of judgment.

Therapeutic Common Sense: Redeploy Withdrawn Officers to Churches, Schools, and Vulnerable Communities

Given the scale of killings, kidnappings, church attacks, school abductions, and rural massacres in Nigeria, therapeutic common sense — and basic security logic — demands that any officers freed from VIP service should be immediately sent to the country’s most vulnerable spaces. In a rational system, the first priority after withdrawing officers from private households would be to post them to schools, especially those in high-risk areas; to churches and mosques that have been repeatedly attacked; to rural communities facing raids; to major highways where kidnappers operate; and to Christian schools and churches that have been singled out by extremists. This is what trauma-informed leadership would look like: identifying where fear is highest and protection is weakest, and then flooding those spaces with visible, disciplined, well-supervised security presence. It would calm anxious parents, reassure congregations, restore some sense of order in rural communities, and send a clear message to attackers that society is no longer unprotected. Instead, what Nigerians often see is motion without direction. Officers are announced as “withdrawn” from VIPs, but the public does not see a corresponding increase in the protection of ordinary people. Civil Defence personnel risk being dragged deeper into private compounds rather than pushed out to guard critical public spaces. There is no coherent strategy that links withdrawal from misuse to redeployment to high-risk zones. This absence of therapeutic, targeted redeployment shows how far leadership thinking is removed from the real emotional and physical needs of the people.

What Pastor Enenche Exposed: Leadership Needs Psychological Testing and Psychiatric Screening

Pastor Enenche’s call for psychiatric evaluation of some leaders may sound extreme, but underneath the rhetoric lies a serious psychological question. When leaders consistently deny obvious realities, trivialize large-scale violence, dismiss genuine grievances, or double down on failed approaches, mental health professionals begin to talk about judgment deficits, impaired reality testing, emotional detachment, and cognitive rigidity. Around the world, high-risk leadership positions — such as military command, intelligence leadership, judicial office, and in some cases top political roles — are increasingly seen as roles that require not only education but psychological fitness. A leader who struggles with empathy, impulse control, emotional regulation, or accurate risk perception can do enormous damage even if he or she holds the highest possible degrees. There is nothing wrong in principle with assessing such people using psychological tests that explore cognitive abilities, executive function, emotional intelligence, personality patterns, and stress management. In extreme cases, psychiatric evaluation may indeed be needed — not as a public insult, but as a private safeguard for the nation. The idea that some Nigerian leaders might benefit from psychological or psychiatric assessment should not be dismissed as mere provocation; it should be considered as one aspect of building a system where responsibility is matched with mental fitness. Education alone cannot guarantee that a leader is emotionally stable, morally grounded, or cognitively sound.

Real-Life Examples That Show Degrees Do Not Equal Intelligence

There are too many real-life examples in Nigeria to sustain the myth that degrees guarantee good leadership. A governor with multiple academic qualifications can stand before cameras and deny ethnic or religious killings that are widely documented, even as victims bury their dead and displaced communities cry out. Another governor can visit camps of displaced people, urge them to “go back home” despite credible reports that armed groups still occupy their villages, and then act surprised when more attacks occur. A minister with foreign degrees can respond to insecurity by blaming abstract “foreign conspiracies” rather than examining obvious weaknesses in local policy and enforcement. A security chief with a doctorate can declare that terrorism is “technically defeated” in the same period that schoolchildren and farmers are being abducted in large numbers. Senators with law degrees can turn the National Assembly into a theatre of physical fights, mace theft, and fence-jumping. Senior police officers can ignore court orders under the excuse of “superior instruction,” as though the constitution were optional. These are not the actions of an uneducated population. They are the actions of educated individuals making senseless decisions. This is not to say everyone in leadership is stupid, but the reality is that far too many decisions coming from the top are soaked in avoidable nonsense. The problem is not that Nigeria lacks educated people in power; the problem is that their education is not translating into rational thinking, ethical courage, or strategic intelligence.

The Judgment Crisis at the Heart of Nigeria’s Insecurity

When insecurity persists for years, it is natural to point to guns, funding, numbers, and logistics. But beneath all of that is a quieter, more dangerous crisis: the crisis of judgment. At every turn in Nigeria’s security story, we see signs that the ability to think clearly and evaluate correctly has broken down. Leaders downplay massacres that send shockwaves through communities. They reframe organized terror as mere “farmer–herder clashes.” They close schools instead of defending them. They misallocate police and Civil Defence officers to private compounds while rural areas bleed. They resist modernizing laws that would allow armed, regulated private security firms to take over VIP protection, even though such models are standard in countries they admire and visit. They announce reforms without building systems to implement them. These are not random mistakes; they form a pattern of consistent misjudgment. The frightening implication is that Nigeria is not only facing bandits, terrorists, and kidnappers; it is also facing a leadership culture in which thinking errors have become normal. In such an environment, even good policies are executed poorly, and even intelligent observations like Galadima’s or Enenche’s are heard, discussed briefly, and then buried under the next wave of poorly thought-out decisions.

The State Police Debate: A Nation Begging for Logic While Leaders Protect Political Fear

For years, Nigerians across every region have demanded the creation of state police. Governors have cried out repeatedly, security experts have insisted on it, traditional rulers have endorsed it, and communities under attack have begged for localized, accountable protection. Yet every Inspector General of Police pushes back, clinging to the centralized structure as though decentralization were a national threat. President Tinubu also appears to be walking the same path — offering soft hints, forming committees, making cautious statements, and delaying any real reform until after elections. The psychology behind this delay is simple: political actors prefer a centralized police force during election cycles, because central control allows for influence, pressure, manipulation, and political advantage. But in times of severe insecurity — when kidnappers, bandits, and terrorists operate freely — common sense shows that Nigeria desperately needs localized policing. Community-aware officers, state-driven intelligence networks, culture-informed patrol strategies, and a policing architecture rooted in local knowledge are not luxuries; they are survival necessities. Every year Nigeria delays state police, more Nigerians die, more communities collapse, and more criminals entrench themselves. The refusal to implement state policing is not an intellectual decision; it is political fear disguised as caution. And once again, it reinforces the central argument of this commentary: Nigeria’s security failures are not about lack of education — they are about lack of judgment and courage in leadership.

A Nation Cannot Rise Above the Quality of Its Thinking

In the end, a country does not rise on the strength of its degrees; it rises on the strength of its thinking. Nigeria is not short of educated men and women in office. What it lacks is a critical mass of leaders whose education has matured into judgment, whose knowledge has transformed into wisdom, and whose exposure has solidified into courage. A society where police and Civil Defence officers are turned into private servants, where schools are shut instead of protected, where churches and communities remain exposed despite years of bloodshed, and where public decisions regularly defy logic, is not suffering from lack of schooling — it is suffering from lack of sound judgment. Until Nigeria is led by people who can reason clearly, anticipate consequences, regulate their emotions, respect the constitution, and prioritize the safety of citizens over the comfort of the elite, no pile of certificates will save it. Real leadership is not about the number of degrees hanging on an office wall; it is about the quality of decisions that flow from the mind and heart of the person sitting behind the desk. Right now, those decisions continue to show that Nigeria’s deepest crisis is not the absence of education, but the absence of intelligence, insight, and judgment where it matters most.

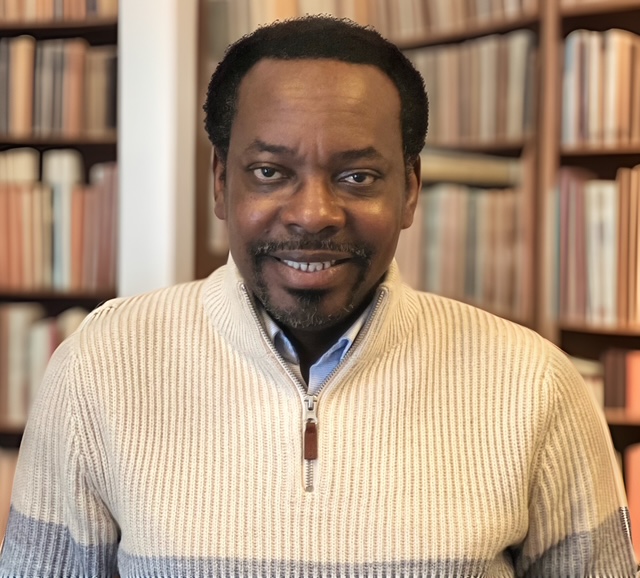

Professor John Egbeazien Oshodi, Clinical/Forensic Psychologist

About the Author

Prof. John Egbeazien Oshodi is an American psychologist and educator with expertise in forensic, legal, clinical, cross-cultural psychology, public ethical policy, police, and prison science.

A native of Uromi, Edo State, Nigeria, and son of a 37-year veteran of the Nigeria Police Force, he has dedicated his professional life to bridging psychology with justice, education, and governance. In 2011, he played a pioneering role in introducing advanced forensic psychology to Nigeria through the National Universities Commission and Nasarawa State University, where he served as Associate Professor of Psychology.

He currently serves as contributing faculty in the Doctorate in Clinical and School Psychology at Nova Southeastern University; teaches across the Doctorate Clinical Psychology, BS Psychology, and BS Tempo Criminal Justice programs at Walden University; and lectures virtually in Management and Leadership Studies at Weldios University and ISCOM University. He is also the President and Chief Psychologist at the Oshodi Foundation, Center for Psychological and Forensic Services, United States.

Prof. Oshodi is a Black Republican in the United States but aligns with no political party in Nigeria—his allegiance is to justice alone. On the matters he writes about, he speaks for no one and represents no side; his voice is guided solely by the pursuit of justice, good governance, democracy, and Africa’s advancement. He is the founder of Psychoafricalysis (Psychoafricalytic Psychology)—a culturally rooted framework that integrates African sociocultural realities, historical awareness, and future-oriented identity. A prolific thinker and writer, he has produced more than 500 articles, several books, and numerous peer-reviewed works on Africentric psychology, higher education reform, forensic and correctional psychology, African democracy, and decolonized models of psychological practice.