Africa

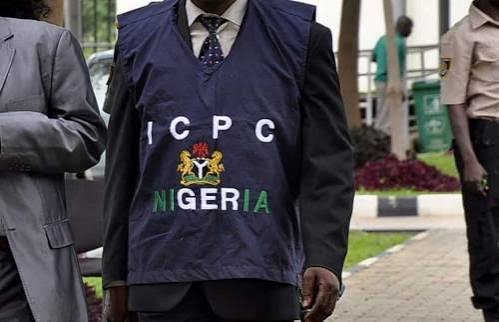

ICPC And The Unfinished War Against Corruption In Nigeria -By Rachael Emmanuel Durkwa

Strengthening ICPC is essential if Nigeria truly seeks to fight corruption from the root rather than merely pruning its branches. For too long, anti-corruption efforts have been reactive and politicized. ICPC can lead a new wave of preventive, systemic reform—if only the nation is ready to give it the independence, funding, and support it deserves. The war against corruption remains unfinished, but with a reformed ICPC, Nigeria might finally begin to tip the scales in favor of integrity.

Corruption in Nigeria is not merely a challenge; it is an institution. It infiltrates politics, administration, business, and even everyday transactions, weakening the moral and structural foundation of society. To tackle this menace, Nigeria has created several anti-graft agencies, among which the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) stands out. Established in 2000, ICPC was designed to prevent, investigate, and prosecute corruption-related offences. Yet, more than two decades later, the jury is still out on whether ICPC has been effective in dismantling corruption or has simply become another cog in Nigeria’s underperforming governance machinery.

Unlike the EFCC, which primarily focuses on financial crimes, ICPC’s mandate is broader. It is tasked with investigating bribery, abuse of office, and all manners of corrupt practices in public institutions. In addition, the commission is mandated to educate Nigerians on corruption’s dangers and to promote integrity in public life. In principle, this dual focus on enforcement and prevention should have made ICPC a game-changer. But in reality, the commission has often been overshadowed by EFCC, struggling to assert its relevance in the crowded anti-corruption landscape.

One of the commission’s major strengths lies in its preventive approach. Through systems studies and public enlightenment campaigns, ICPC has attempted to identify loopholes in ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs) that enable corruption. For example, its annual reports often highlight how poor record-keeping, weak procurement processes, and opaque recruitment practices fuel corrupt behavior. By addressing these systemic issues, ICPC recognizes that corruption is not only about individuals but about flawed institutions. Unfortunately, the preventive approach does not grab headlines like dramatic arrests, which explains why ICPC remains less visible to the public.

Still, ICPC faces serious limitations. A fundamental challenge is the lack of political will to support its work. Corruption in Nigeria is deeply entrenched at the highest levels of government, and anti-graft agencies are often pressured not to touch politically exposed persons. While ICPC has recorded convictions, most involve low- to mid-level officials. Rarely do we see powerful politicians or high-ranking bureaucrats face the full weight of ICPC prosecutions. This selective enforcement fuels the perception that Nigeria’s anti-corruption war is toothless, and worse still, designed only to target the powerless.

Another challenge is underfunding and inadequate manpower. ICPC is expected to oversee thousands of public institutions across the federation, yet it lacks the resources to carry out its mandate effectively. Investigations require expertise, technology, and logistical support, but budgetary allocations are often insufficient. This underfunding not only hampers operations but also leaves the commission vulnerable to compromise. A poorly funded anti-graft body cannot outmatch the sophisticated networks of corruption it seeks to dismantle.

Public perception also remains a stumbling block. Many Nigerians are either unaware of ICPC’s role or dismiss it as irrelevant compared to EFCC. The commission has not done enough to establish its visibility, especially in the digital age where citizen engagement is crucial. Its enlightenment campaigns are often limited to sporadic workshops or media jingles, which are insufficient to change entrenched behaviors. If corruption is a cultural problem in Nigeria—as many believe—then ICPC must scale up its public education role to instill values of integrity, especially among the youth.

The judiciary, once again, is another weak link in ICPC’s chain. Trials for corruption cases are slow, bogged down by adjournments and technicalities. Even when ICPC secures convictions, appeals often drag on for years. The absence of special anti-corruption courts weakens deterrence, allowing offenders to exploit the system. Unless Nigeria reforms its judicial processes to fast-track corruption trials, both ICPC and EFCC will continue to achieve limited impact.

But beyond challenges, ICPC has demonstrated potential. Its “Ethics and Integrity Compliance Scorecard” for MDAs is a commendable innovation. By ranking government agencies based on transparency and accountability, it creates pressure for institutions to improve their practices. Similarly, its work with tertiary institutions to combat academic corruption—such as examination malpractice, sexual harassment, and illegal admissions—shows a willingness to tackle corruption at grassroots levels. These are important contributions, even if they do not always receive the recognition they deserve.

Yet, the question remains: how can ICPC be more effective? First, its independence must be strengthened. Leadership appointments should not be subject to political influence, and the commission must have prosecutorial freedom without fear of interference. Second, its funding must be significantly increased to enable nationwide operations. Third, ICPC must embrace technology more aggressively. Digital monitoring systems, whistleblower apps, and e-governance platforms can help reduce opportunities for corruption and make its work more impactful.

More importantly, ICPC must double down on its preventive mandate. Unlike EFCC, which often chases corruption after it has occurred, ICPC has the unique opportunity to stop corruption before it happens. This means intensifying public education campaigns, embedding integrity into school curricula, and working closely with civil society to change the culture of impunity. Corruption in Nigeria is not just a crime; it is a social disease. Treating it requires not only prosecutions but also a moral reawakening.

In conclusion, ICPC is an institution with promise but one that has not fully delivered on its mandate. It is caught between lack of resources, political interference, and a hostile environment where corruption thrives. Yet, Nigeria cannot afford to abandon it. Strengthening ICPC is essential if Nigeria truly seeks to fight corruption from the root rather than merely pruning its branches. For too long, anti-corruption efforts have been reactive and politicized. ICPC can lead a new wave of preventive, systemic reform—if only the nation is ready to give it the independence, funding, and support it deserves. The war against corruption remains unfinished, but with a reformed ICPC, Nigeria might finally begin to tip the scales in favor of integrity.

Rachael Emmanuel Durkwa is a 300 level Student from Mass Communication Department University of Maiduguri (UNIMAID)