Politics

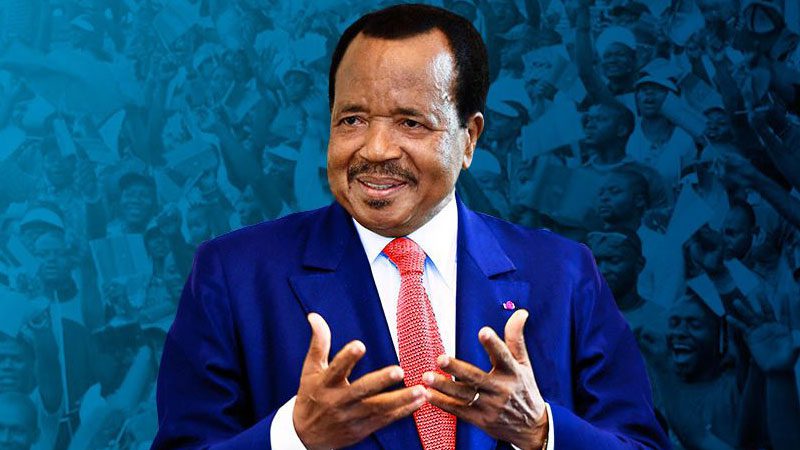

If Paul Biya Loses, It’s A Win For African Democracy, If He Wins, It’s A Loss For It -By Isaac Asabor

Cameroon stands today at a crossroads, but so does Africa. The continent’s democratic credibility depends not on what Biya does, but on what the people allow.

It is no more news that Paul Biya and his closest rival, Maurice Kamto of the Cameroon Renaissance Movement (CRM), are both claiming victory in the just concluded presidential election, plunging the country into a tense post-election standoff. While Biya’s camp insists that the longtime incumbent has secured yet another term, Kamto maintains that the people’s will favors change, not continuity. The conflicting claims have set the stage for deep political uncertainty, raising fears that the fragile calm in Cameroon could collapse into unrest if the dispute is not handled with transparency and restraint.

Given the foregoing backdrop, it is not an exaggeration to opine that Cameroon is bracing for yet another controversial election under President Paul Biya as the question confronting Africa is no longer whether he will win or loses, but what either outcome means for the continent’s fragile democracy.

Few African leaders personify the corrosion of democratic principles like Biya, the 92-year-old ruler who has clung to power since 1982. For over four decades, he has ruled Cameroon with an iron hand, outlasting coups, Cold War transitions, and the rise and fall of multiple African governments. His reign, however, has done little to improve the lives of ordinary Cameroonians.

If Biya finally loses power, it will mark a historic turning point, not just for Cameroon, but for the entire continent. It would mean that even Africa’s most entrenched autocrats can still be unseated by the will of the people. If he wins again, it would represent another painful reminder that African democracy, despite its rituals and rhetoric, remains hostage to leaders who mistake tenure for destiny.

Without resort to denigration of his person, Biya is a man who mistook power for birthright. This is as he has ruled Cameroon since November 1982, following the resignation of Ahmadou Ahidjo. In the years since, he has cultivated the image of a quiet technocrat while operating one of the most repressive political systems in Africa. Under his watch, elections have become predictable ceremonies rather than genuine contests, while state institutions have been bent to serve the president’s personal interests.

His long rule has come to symbolize the very crisis of leadership that haunts post-independence Africa, longevity without legitimacy, power without progress, and governance without accountability.

To put Biya’s 43-year rule in perspective, it is germane to opine that Cameroon has had one president since Nigeria witnessed the fall of three republics, Ghana moved through several democratic transitions, and South Africa went from apartheid to full democracy. When Biya took power, the Berlin Wall still stood, and Nelson Mandela was still in prison.

In 2025, the question Cameroonians are asking is not who will win, but whether the people’s voice will ever be allowed to count.

Without any iota of exaggeration, the political situation in Cameroon at the moment is a chance for redemption, if he loses.

If Biya loses, it would be a watershed moment for Cameroon and Africa alike. It would demonstrate that no leader, no matter how entrenched, is immune to democratic accountability.

In fact, a Biya defeat would send shockwaves through the continent’s corridors of power. It would embolden citizens in countries like Nigeria, Uganda, Congo-Brazzaville, and Equatorial Guinea, nations where presidents have turned power into private property, to believe once again in the potency of the ballot.

For Cameroon, a Biya loss would offer the chance to heal decades of wounds. The Anglophone crisis, which has festered since 2016, could finally be addressed with sincerity rather than repression. The country’s youth, many of whom have known no other leader, could begin to dream again of a government that listens, not dictates.

Africa needs such victories. They remind us that democracy is not a Western concept but a universal aspiration, the simple belief that power belongs to the people, not the palace.

In African politics, longevity is often mistaken for stability. Biya’s defenders argue that his 43-year reign has kept Cameroon from descending into chaos. But stability built on fear, manipulation, and repression is not peace, it is paralysis.

Biya’s government has survived by crushing dissent, controlling the press, and weakening opposition through divide-and-rule tactics. His electoral victories have been marred by allegations of fraud, intimidation, and abuse of state machinery.

His regime epitomizes a wider continental disease: leaders who enter office through elections and then spend decades perfecting how to never leave. In this, Biya stands alongside figures like Teodoro Obiang Nguema of Equatorial Guinea and Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, leaders whose countries have known no other ruler for generations.

If Biya loses, it will prove that even in Africa, where power is often guarded like a family heirloom, citizens can still rise above fear to demand change.

If, however, Biya “wins” again, as he has so many times before, it would mark yet another defeat for the democratic process. It would send a dangerous message across the continent: those elections in Africa remain mere rituals designed to validate power, not challenge it.

Every time Biya wins, democracy loses a little more credibility. Each victory deepens cynicism among young Africans who already doubt that the ballot box can ever deliver genuine change.

When a leader who has overseen decades of corruption, repression, and economic decay continues to “win,” it is not a reflection of public support; it is proof that the system has been hijacked. It tells the continent that elections are no longer instruments of choice, but performances of control.

And every such “victory” emboldens other rulers who share Biya’s autocratic instincts. They see his longevity as validation, evidence that democracy can be weaponized to legitimize dictatorship.

At 92, Biya represents more than just political endurance; he represents moral decay. He has become a metaphor for the exhaustion of post-independence leadership in Africa.

For years, he has been accused of governing from luxury hotels in Switzerland while his country bleeds. Cameroon’s roads crumble, its hospitals decay, and its youths flee in droves in search of opportunity. The Anglophone regions remain militarized, and poverty continues to rise.

Yet Biya’s grip endures, fueled by a system built on patronage, fear, and the manipulation of ethnic loyalties. His continued rule mocks the very idea of accountability, and exposes the hollowness of the term “democracy” in nations where elections are only symbolic.

If democracy is about choice and renewal, then Biya’s Cameroon is its opposite: a cautionary tale of how power can fossilize into tyranny.

Biya’s political fate carries weight far beyond Cameroon’s borders. His fall would rekindle hope across a continent where leaders routinely amend constitutions to elongate their stay in power. From Zimbabwe’s Mugabe to Sudan’s al-Bashir, history has shown that no ruler is invincible.

But Biya’s continued survival in office threatens to reverse those lessons. It encourages the perception that Africa is trapped in an endless cycle of recycled leadership, that democracy here is not about governance, but about longevity.

If Biya loses, it could spark a renewed continental conversation about leadership turnover, accountability, and institutional strength. It would affirm that democracy in Africa can still evolve, that the people, not the palace, have the final say.

If he wins, it would be a reminder that Africa’s biggest obstacle to progress is not poverty or illiteracy, but the refusal of its leaders to step aside.

Whatever happens in Cameroon, Paul Biya’s legacy is already sealed. History will not remember him as a builder, but as a man who stayed too long, mistaking the state for his property.

If Biya loses, it will be a victory not just for Cameroon but for the African spirit, the idea that even after decades of repression, the will of the people can still prevail. It will mark the end of an era and the rebirth of hope.

But if he wins, it will be another dark day for African democracy, proof that the continent’s political systems remain vulnerable to manipulation by those who should be their custodians. It will mean that democracy, in too many African countries, remains a promise unfulfilled.

Cameroon stands today at a crossroads, but so does Africa. The continent’s democratic credibility depends not on what Biya does, but on what the people allow.

If he loses, it will be the sound of freedom echoing through the continent. If he wins again, it will be the echo of democracy gasping for breath.

And in that moment, the verdict will be clear: when Paul Biya loses, Africa wins; when he wins, Africa loses.