Africa

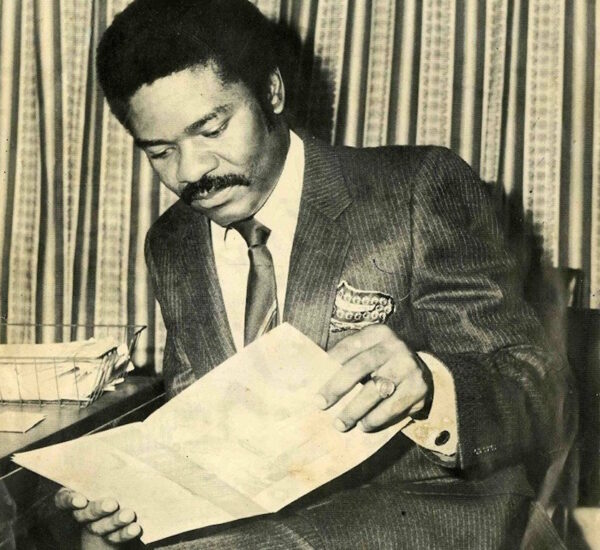

Remembering Dele Giwa -By IfeanyiChukwu Afuba

After 25 years of uninterrupted democracy, the impression that Nigeria has outgrown coups is tempting. No doubt, accountable administration could be hard to achieve with elected government but it’s much worse with military rule. Now that history is back as subject of study in secondary education, it will hopefully lead younger generations to appreciation of dimensions of our national journey.

It’s incumbent on Nigerians not just to protect constitutional order but to ensure that democracy translates to good governance.

Sunday, October 19, 2025 marked 39th anniversary of the brutal killing of ace journalist, Dele Giwa. October 19, 1986, the day Dele Giwa was assassinated via a parcel bomb was also a Sunday. In that serene mood of a Sunday morning, the plotters sneaked up to their act, shattering the peace of the day as well as the celebration trailing Wole Soyinka’s reception of the Nobel Prize for literature. The incident quickly assumed national, international interest both for Giwa’s standing as a leading journalist and sophistication of the operation. Fingers were pointed at the military government. The immediate circumstances of the incident raised curiosity. Giwa, on taking up the parcel had reportedly said it must be from Dodan Barracks, the seat of power. Giwa’s intuition fitted with the perception that state security agencies were about the only actors with the reach to execute such an operation. But there were also remote considerations, with implications for state, society and the media – till date and foreseeable future.

Dele Giwa’s treatment has to be situated in the context of government – media relations. Shortly before the tragic event of October 19, the Newswatch editor had made a complaint to his lawyer, Gani Fawehinmi, about accusations of gun – running made against him by the secret police. The encounter with the State Security Service left the feisty journalist downcast. He was worried by the calculation that if the secret police could make such an explosive fabrication against him, it followed he was a marked man. Dele Giwa was a full time journalist and it could be said that his passion for the craft had just found full expression at the time. On return from the United States where he studied and worked for a while, Giwa pitched his tent with _Daily Times_ . It was the outstanding newspaper of the 1970s and early 80s. But it’s rating was limited by the fact of government ownership. As much as the paper tried to be detached from government, the tag never fell off. It’s a measure of Giwa’s stuff that under the circumstances, he still made an impression with his writings at the _Times_ . Journalistic freedom seemed greater at _Concord_ newspapers where Dele Giwa became one of the founding staff in 1980. Privately owned, Concord was profit – driven. It’s ‘free enterprise’ ideology promised to unleash new energy into journalism practice. And with a mix of vision and verve, the Concord brand caught on. Concord was confident and Giwa’s columns bold. Circulation rose rapidly and with it, fame for the paper’s leading lights.

But there was a snag. Concord titles publisher, Moshood Abiola was a politician and stalwart of the ruling party. The development journalism implied in the paper’s name, national concord, somewhere along the line, conflicted with the publisher’s political partisanship. Concord’s expose of contradictions in the opposition’s activism, reflected vistas of investigative journalism but pursuit of the same subject over a long period seemed divisive, a witch-hunt. Giwa and his comrades’ association with Abiola’s political obsession posed a challenge to an otherwise brilliant career. It was no surprise that shortly after, Dele Giwa and his colleagues seized the opportunity to launch into independent media practice. And _Newswatch_ was born in 1985. It was not the first, (serious) newsmagazine. Earlier post – independence journalism had served _Afriscope_ and _Newbreed_ . But it was the first newsmagazine modelled after America’s _Time._ _Newswatch_ was modernist, stylish, investigative, analytic. For the most part, the tone was cautionary. ‘Shagari’s Last Days’, a rich fusion of news, analysis and history, is one of the memorable stories of the early years. In just two years, Newswatch had become influential and perhaps, authoritative, too.

And that mileage became a problem. Government began to pay closer attention to the contents of the publication; to evaluate and analyse the magazine’s offerings. It was a military regime ordinarily at odds with citizenship rights and press freedom. With Newswatch’s urbane commentary, the tragedy of October 19, 1986 might have been averted – but for two elements. First, Giwa had a style of his own that could be described as irreverent. The pages of the magazine veered between moderated lines and the caustic columns of Giwa and occasionally, Ray Ekpu, Dan Agbese and Yakubu Mohammed. A number of Dele’s writings came across as strong but it would appear that a particular essay on the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) was punchy. The contentious lines read: “If SAP fails, the masses will stone the authors of the policy.” It was understood that the intelligence agencies interpreted the statement as incitement against the authorities. Secondly, the military government had a sense of politics.

The Ibrahim Babangida – led junta was just thirteen months in power by October 1986. But it was a regime especially sensitive to public approval. The junta, on coming to power, had gone out of it’s way to launch a public relations campaign. No effort was spared in portraying the regime as liberal, in contrast to the immediate past dictatorship. In one of their posturings, detention centres were flung open and detainees released by the new junta on seizing power, August 27, 1985. Maintaining the illusion of openness, the regime threw the IMF loan proposal and the country’s political future open for public debate.

But in a move to endear itself to the core muslim north, the middle belt – leadership of the regime did not consult Nigerians as the country became a member of Organisation of Islamic Countries, in coup – like fashion. In any case, the popular verdicts from the national debates were soon cast aside for the junta’s predetermined positions.

Given the military government’s predilection for self reversal, many doubted the essence of SAP, it’s viability, durability. While economic recession is a condition that afflicts all countries at some points, there’s a strong case that Nigeria’s development bane is fundamentally about indiscipline and corruption. Ignoring this twin diseases for all manner of reforms is akin to erecting a superstructure on cracking, leaking structure. Attempts by the Buhari – Idiagbon regime, though bordering on the fascistic, at making actors in the second republic accountable, was being discontinued. Same for the overthrown regime’s crude war against indiscipline. The prosecutions were faulty, but the principle healthy. Contrastingly, Nigerians did not observe a sense of frugality on the part of the government subjecting them to hardship for a better tomorrow. Few years earlier, general Olusegun Obasanjo as Head of State ran ‘low profile’ administration in response to declining economic fortunes. Towards the end of his tenure, President Shehu Shagari introduced ‘austerity measures’ in effort to cut government spending. In that supposedly setting of fiscal discipline, the Babangida regime continued with huge spending. Infrastructure works were accelerated in Abuja, the third mainland bridge undertaken in Lagos. Nigeria embarked on the Technical Aid Corps, funded activities of OAU and bankrolled operations of Ecomog, the ECOWAS military force.

With a mono economy, little or no exports, high government spending, deficit budgetary financing, system leakages and corruption, SAP inflicted suffering and social distress on the citizenry. It marked the beginning of the threat to the middle class. At a time a graduate’s monthly salary was about four hundred naira, the price of a small, black and white television set jumped to eight hundred naira. By 1986, unemployment was prevalent, leading to the creation of National Directorate of Employment. The financial crisis was captured humorously in a cartoon by The Guardian’s Obe Ess sometime in 1988. It was an advertisement of a brand new Jetta car. For each of the features of the car, the response was ‘amazing.’ A litany of ‘amazing’ continued until the cartoon came to the last item, the price of the car,l. Fifty – two thousand naira! ‘Amusing’ was the last word. The introduction of SAP marked the gradual end of educational and fuel subsidies. SAP as economic restructuring did fail as darkly predicted. And there were several SAP riots between 1987 and 1990.

After 25 years of uninterrupted democracy, the impression that Nigeria has outgrown coups is tempting. No doubt, accountable administration could be hard to achieve with elected government but it’s much worse with military rule. Now that history is back as subject of study in secondary education, it will hopefully lead younger generations to appreciation of dimensions of our national journey.

It’s incumbent on Nigerians not just to protect constitutional order but to ensure that democracy translates to good governance. Government – media relations should not be taken for granted but continually cultivated for the common good of state and society. Nigeria can set up a standing body for purpose of promoting government – media dialogue and cooperation. Closer interaction and exchanges on the expectations of each side will aid better understanding of institutional practices as well as limits.