Africa

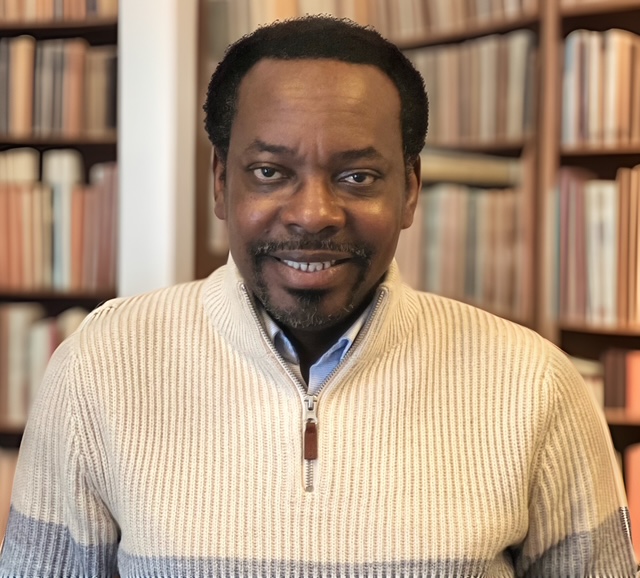

2025 UTME And Our Fault Lines -By Zayd Ibn Isah

The real tragedy in all of this is not merely that a technical error marred the 2025 UTME, but that it instantly became a mirror reflecting our lingering distrust of one another. Until we begin to see ourselves first as Nigerians, beyond tribe, tongue, or region, these fault lines will not only persist, they will widen.

I have never seen a country so united, yet so divided at the same time, as Nigeria. If you want to see how united Nigerians can be, let the Super Eagles compete against another country—like the Bafana Bafana of South Africa, in a soccer match. You would see just how loudly Nigerians on social media would speak with one voice to support their team. Or if a Nigerian attempts to break a record, such as when Hilda Baci took on the Guinness World Record for the longest cooking marathon, you would see how Nigerians would rally behind the person, regardless of their tribe or religion. But when it comes to issues of national concern, our reactions reveal us not only as a people still living in denial, but also clinging onto ingrained prejudices and beliefs.

This was the case with the recently released 2025 UTME results, where more than half of the candidates performed below par. Stakeholders pressured the examination board to come clean, describing the mass failure as unprecedented in JAMB’s history. Surprisingly, the JAMB Registrar, in a rare act of personal accountability, admitted that a technical error had compromised the outcome of the examination. He offered to conduct a resit for the affected students. However, if he thought that admitting fault would calm public outrage, he was mistaken. It only aggravated the situation. It was like pouring kerosine on an already raging fire, as aggrieved individuals demanded his resignation. Many insisted that the honourable thing would be to step down and allow an independent investigation into the root and immediate causes of the failure, rather than shedding crocodile tears.

Soon, the issue escalated into a regional outcry. Some compatriots from the South East viewed it as a case of deliberate sabotage, claiming their region was the worst affected. They even revived the case of Ejikeme Mmesoma, the young girl who had claimed the highest UTME score in 2023. Some now argue that perhaps she hadn’t lied after all, and that JAMB had only victimised her because she is from Alaigbo.

This is how divided we are, even on matters of serious national concern. Yet those trying to exonerate Mmesoma based on this year’s incident fail to acknowledge a critical fact: the actual highest scorer in that same 2023 examination was also an Igbo girl.

There is no gainsaying the fact that, as JAMB Registrar for nine years and counting, Professor Ishaq Oloyede has delivered results. Even those calling for his resignation cannot deny that. The technical error is, no doubt, unacceptable, and we are right to be angry, because the future of our tomorrow’s leaders is at stake. But at the very least, incidents like this should call for sober reflection, rather than further deepen our fault lines.

Unfortunately, this tendency to retreat into ethnic and regional enclaves is not limited to education. We have seen it play out repeatedly in other sectors. Conflicts between herders and farmers across the Middle Belt and Southern Nigeria continue to drive a wedge between ethnic groups. What began as disputes over land and resources has now taken on deeply ethnic and religious overtones. Many in the South accuse the federal government of bias or inaction, particularly when it appears to favour one region.

The Boko Haram insurgency in the North East, ongoing for more than a decade, has further exposed regional disparities in national empathy. Northerners often feel abandoned by the rest of the country, while some Southerners believe the crisis is being used to justify disproportionate federal funding.

The Federal Character principle and quota system, originally designed to promote inclusivity, have also become flashpoints. Many Southerners argue that these policies punish merit and excellence, especially in federal recruitment and university admissions. Meanwhile, Northerners see them as essential to correcting historical imbalances. Even our responses to national tragedies vary based on geography. When students are kidnapped in the North, national outrage is often subdued compared to similar incidents in the South, or vice versa. It is almost as if our empathy is shaped by where the victims come from.

These are not just cracks in our unity. These are strong indicators of deep and dangerous fault lines. The fact that our collective nationhood has rested upon such a fragmented foundation (for over 60 years!) is nothing short of a miracle. It is saddening that when issues that should inspire collective action instead become opportunities for ethnic or regional point-scoring, it reveals just how fragile our national identity remains. Remember how in 2011, the former U.S. ambassador to Nigeria, John Campbell, predicted that Nigeria would not exist beyond 2015? At the time, this caused many people to be apprehensive and paranoid, especially with the state of the nation at the time. To such people, the disintegration of Nigeria was an inevitability.

Thirteen years since Campellʼs damning prediction, Nigeria is still very much a country, going through difficult times, but still whole. The journey down to this present age has been anything but easy. But along the way, this nation of numerous ethnicities has survived a civil war, decades of military rule and internal threats to its integrity as a country. And it is my belief that we will also survive modern-day agents of division who constantly stir up theories to fan the flames of distrust and irrationality that threaten our national unity.

We have crossed several milestones as a country, and if that is not an indication of our collective will, strength and grit, then I don’t know what it is at all. At this point, the Nigerian government, other than countering the centrifugal drives of divisive elements amongst us, also needs to prioritise transparency and inclusivity in its handling of our affairs, if only to shoot down conspiracy theories.

Agreed, like any other society, we are not without our flaws. But just like the actions of a few should never be allowed to define the many, the missteps of a national agency should not be overblown as proof of sinister plots to marginalise or punish certain regions. Such claims are simply ridiculous and should not be entertained in any meaningful discourse. We should only pay mind to conversations that would strengthen our bond, or help us find solutions on our journey as a nation.

The real tragedy in all of this is not merely that a technical error marred the 2025 UTME, but that it instantly became a mirror reflecting our lingering distrust of one another. Until we begin to see ourselves first as Nigerians, beyond tribe, tongue, or region, these fault lines will not only persist, they will widen.

Zayd Ibn Isah can be reached at lawcadet1@gmail.com