Africa

2026 Tax Reforms: Relief for the Poor or a Squeeze on Nigeria’s Middle Class? -By Abdulhamid Rabiu

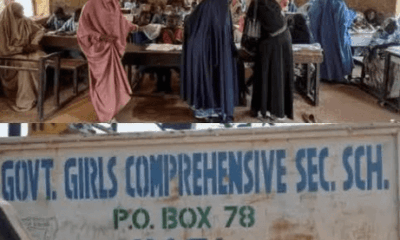

Nigerians are repeatedly asked to pay more, yet roads are unsafe, public hospitals are overstretched, schools shut down over strikes, and insecurity remains widespread. When taxes do not translate into visible services, citizens see taxation not as a civic duty, but as an unfair demand.

2026, Nigeria’s tax reforms will move from policy promises to lived reality. The Federal Government says the changes are designed to protect low-income earners, widen the tax base, and boost non-oil revenue. Yet for millions of Nigerians already struggling to stay afloat, the real question is simple: who truly pays the price?

At a time of rising inflation, weak purchasing power, and post-subsidy economic shocks, tax policy is no longer an abstract economic tool. It is now deeply personal.

The Case for Reform

Government officials argue that Nigeria’s tax-to-GDP ratio remains among the lowest globally, making reforms unavoidable. The 2026 tax direction includes exemptions for minimum wage earners, adjustments to personal income tax, and tighter enforcement through digital systems.

On the surface, these measures appear fair. Protect the poorest, demand more accountability, and reduce dependence on oil revenue. But policy success is not measured by intention—it is judged by impact.

A Middle Class Under Pressure

Nigeria’s middle class has become the economy’s silent casualty. Civil servants, professionals, and small business owners now face rising transport costs, higher electricity tariffs, increasing rent, school fees, and healthcare expenses.

For this group, taxation is unavoidable. Their incomes are visible, salaries are taxed at source, and compliance is mandatory. While the wealthy often find legal loopholes and the informal sector remains largely untaxed, the middle class carries the burden.

The danger in the 2026 tax reforms is not what they remove for the poor, but what they quietly add for everyone else.

Tax Without Trust

Perhaps the greatest weakness of Nigeria’s tax system is not policy design but public trust.

Nigerians are repeatedly asked to pay more, yet roads are unsafe, public hospitals are overstretched, schools shut down over strikes, and insecurity remains widespread. When taxes do not translate into visible services, citizens see taxation not as a civic duty, but as an unfair demand.

A functional tax system depends on a social contract. In Nigeria, that contract feels broken.