Africa

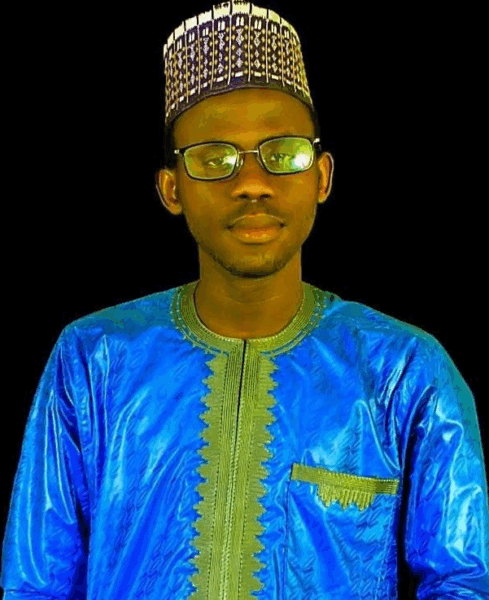

Debt Dynamics and Fragile Growth: Rethinking Nigeria’s Borrowing Model -By Abbas Haruna Idris

Debt can be a tool for development if wisely managed. But if Nigeria continues to borrow without building, the future will be mortgaged to creditors while citizens inherit only fragility. The cost of borrowing is therefore not just financial; it is existential for a nation struggling to find its path to sustainable growth.

Every generation of Nigerian leaders has promised that borrowing is a bridge to growth. Loans are often justified as instruments for building infrastructure, financing reforms, and creating opportunities. Yet, the paradox of Nigeria’s experience is that borrowing rarely translates into development. Instead of growth, the country experiences fragility.

Instead of prosperity, it inherits debt traps. The narrative of debt is not only about numbers but also about the deeper structures of governance, political choices, and economic models that determine whether borrowed funds strengthen or weaken the nation.

Nigeria today faces a familiar yet more intense challenge: a fragile economy sitting on the weight of rising debts. The removal of fuel subsidies in 2023, the decision of the Tinubu administration to continue borrowing, and the historical record of Buhari’s unprecedented debt accumulation all highlight a central question: how does a country borrow responsibly in an economy that is already fragile?

The answer lies in understanding the dynamics of debt. This is not only about fiscal mathematics but also about political economy, theories of development, and comparative lessons from Africa.

Nigeria’s debt story is long and chequered. In the 1980s, during the structural adjustment programmes (SAP) championed by the IMF and World Bank, Nigeria entered a cycle of austerity and borrowing that reshaped its economy. The SAP period institutionalised the culture of external dependence and foreign prescriptions.

By the early 2000s, debt had become a defining national crisis until the historic debt relief negotiated by President Obasanjo in 2005 under the Paris Club initiative. That relief was meant to give Nigeria a clean slate, to redirect resources toward growth.

Yet within two decades, Nigeria has returned to debt levels comparable to the pre-relief era. The Buhari government, which came into office in 2015, justified heavy borrowing as a necessity for infrastructure. His administration argued that borrowing was preferable to taxation in a country with a struggling middle class.

Debt stock rose from about 12 trillion naira in 2015 to over 46 trillion naira by 2023. Buhari also relied heavily on Eurobonds, loans from China, and multilateral institutions. While some infrastructure projects emerged, such as railways and roads, they were too few to offset the scale of debt servicing obligations.

Tinubu inherited this fragile balance sheet in 2023. His government removed fuel subsidies, arguing that the savings would stabilise the fiscal system. Yet, without robust revenue reforms and with the continuation of borrowing, Nigeria’s debt burden continues to expand.

Several theories provide insight into Nigeria’s debt dynamics.

Dependency theory argues that developing countries are structurally subordinated to global financial systems. Loans, though presented as instruments of development, perpetuate dependence by tying developing economies to external creditors and conditionalities. Nigeria’s repeated reliance on Eurobonds and multilateral agencies fits this model.

Debt trap theory highlights how borrowing beyond sustainable thresholds leads to a vicious cycle where new loans are taken primarily to service old ones. Nigeria already spends over 90 percent of its revenue on debt servicing, a figure that confirms the trap.

Fiscal illusion theory explains how governments understate the real costs of borrowing while overstating the benefits of projects supposedly financed by loans. Citizens are given the illusion of progress through promises of future infrastructure, while in reality debt obligations eat into social spending.

These theories expose a key truth: Nigeria’s problem is not debt in itself but the lack of a credible borrowing model. Debt can finance growth if invested in productive sectors. But debt becomes destructive if it only finances consumption, political patronage, or poorly executed projects.

Buhari’s administration defended borrowing as a developmental necessity. Major projects such as the Lagos-Ibadan railway and Abuja-Kaduna railway were financed through external loans, often from Chinese credit lines. Supporters of Buhari argued that infrastructure would create the conditions for growth. Yet the numbers tell a different story.

Between 2015 and 2023, Nigeria’s debt service-to-revenue ratio ballooned. Infrastructure projects, while visible, were insufficient to justify the massive liabilities. Roads remained unfinished, railways required subsidies, and electricity projects failed to resolve the chronic power deficit.

Moreover, borrowing was accompanied by a shrinking of the manufacturing sector, inflationary pressures, and currency instability. The naira fell dramatically despite the supposed infrastructure investments.

Buhari’s borrowing exposed the contradiction between developmental rhetoric and fiscal reality. The debt dynamics he created were less about productive expansion and more about fragile growth.

When President Tinubu removed fuel subsidies in 2023, he presented it as a bold fiscal reform. The logic was that Nigeria could not continue to subsidise fuel while borrowing heavily. Removing subsidies would free funds for investment in infrastructure and social services.

Yet, the gamble has produced painful consequences. Fuel prices tripled, inflation surged, and transportation costs crippled households. The savings from subsidy removal have not been transparently channelled into visible projects. At the same time, Tinubu’s government has sought new loans from the World Bank and IMF, as well as issuing more Eurobonds. In effect, borrowing continues even as citizens bear the cost of subsidy removal.

The risk is that Nigeria is creating a dual crisis: fiscal austerity on the poor while debt obligations increase. This deepens fragility rather than stabilises the economy.

Nigeria is not alone. Across Africa, debt crises have resurfaced as governments borrow to fund development in fragile contexts.

Ghana entered multiple IMF programmes after debt servicing consumed most of its revenue. In 2022, Ghana defaulted on external debt and had to restructure bonds. The cedi collapsed, and inflation soared above 50 percent. Ghana’s experience shows how quickly a country can slide from borrowing for development to a debt trap when fiscal discipline is absent.

Angola relied heavily on Chinese loans backed by oil exports. While this financed infrastructure, it also exposed Angola to commodity price volatility. When oil prices crashed, Angola struggled to repay, leading to IMF interventions. Nigeria risks a similar fate since oil remains its major revenue source.

Egypt has borrowed heavily from the IMF and Gulf states. Its currency crises in 2022 and 2023 revealed the fragility of external-debt-driven growth. Despite large loans, the Egyptian economy has struggled with high inflation and social discontent.

These cases underline a central lesson: borrowing without structural reforms leads to fragility, not sustainable growth.

Beyond numbers, debt has human costs. When debt servicing consumes most revenue, governments slash social spending. In Nigeria, education and health are underfunded while billions go to creditors. Poverty rates have risen, unemployment remains high, and inflation has eroded wages.

Intergenerational costs also emerge. Today’s borrowing becomes tomorrow’s obligation for future Nigerians. Children yet unborn inherit fiscal chains created by present mismanagement. Debt, therefore, is not neutral; it is a transfer of responsibility from weak leadership today to vulnerable citizens tomorrow.

The irony is that borrowing often benefits the elite more than the masses. Contracts funded by loans are awarded to politically connected firms. Rentier elites capture the benefits while citizens bear the repayment burden. Debt servicing primarily enriches foreign creditors, while local oligarchs profit from inflated contracts.

This reflects a class politics of debt: the poor subsidise the elite through austerity and inflation, while the elite secure rents from borrowed funds.

There are African examples of more disciplined borrowing. Rwanda, though criticised for authoritarian politics, has invested loans in productive sectors such as ICT, tourism, and infrastructure that generate returns. Botswana has avoided reckless borrowing, relying instead on prudent management of diamond revenues.

These cases show that borrowing can be beneficial if anchored in growth sectors, transparency, and accountability. Nigeria’s failure lies not in borrowing itself but in how borrowed funds are managed.

To rethink borrowing, Nigeria must adopt a new model anchored in three pillars:

Productive Investment: Loans should target sectors with measurable returns such as agriculture value chains, energy, and technology. Borrowing for recurrent expenditure or consumption must be avoided.

Fiscal Discipline: Revenue reforms are essential. Nigeria’s tax-to-GDP ratio remains one of the lowest in Africa. Expanding the tax base fairly and plugging leakages will reduce reliance on debt.

Transparency and Accountability: Citizens must see where loans go. Projects funded by debt should be monitored, audited, and evaluated publicly. This will restore confidence and reduce corruption.

Without these reforms, Nigeria’s debt dynamics will continue to produce fragile growth.

Nigeria’s debt story is not unique but it is urgent. The Buhari administration expanded borrowing to historic levels without delivering structural transformation. The Tinubu administration continues the cycle under the guise of reform. Across Africa, the pattern is the same: fragile economies borrow, creditors profit, and citizens suffer.

Theories of dependency, debt trap, and fiscal illusion explain the cycle. Yet Nigeria is not condemned to fragility. A different borrowing model is possible, one that prioritises productive investment, fiscal discipline, and accountability.

Debt can be a tool for development if wisely managed. But if Nigeria continues to borrow without building, the future will be mortgaged to creditors while citizens inherit only fragility. The cost of borrowing is therefore not just financial; it is existential for a nation struggling to find its path to sustainable growth.

Abbas Haruna Idris is a Nigerian writer and public affairs analyst with a keen interest in political economy, governance, and African development. He is particularly focused on fiscal policy, debt sustainability, and the political economy of reforms in Africa. He writes from Kwarbai Zaria city and can be reached at abbasharun2020@gmail.com