Forgotten Dairies

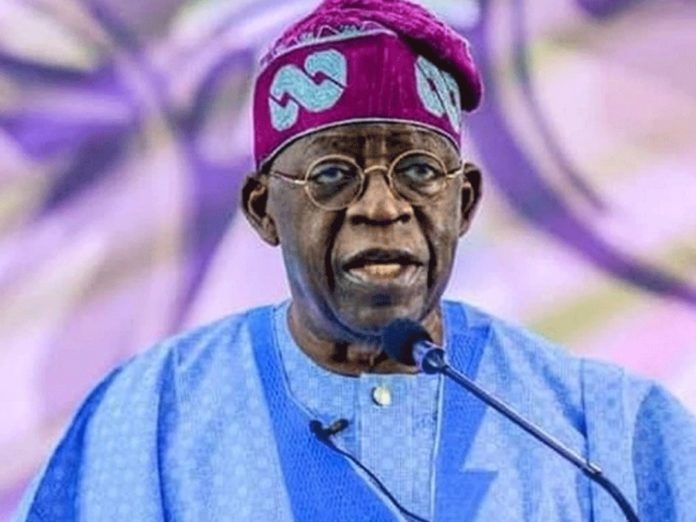

Leadership Without A Base? Tinubu, Wike And The Limits Of Political Authority In Rivers -By Isaac Asabor

If Wike is to be Rivers’ political leader, let it be clearly defined: through party alignment, formal roles, or negotiated consensus within an identifiable platform. Anything else turns leadership into a personal privilege rather than an institutional reality.

President Bola Tinubu deserves credit for stepping in, again, to halt what was fast becoming a slow-motion institutional wreck in Rivers State. By ordering an immediate stop to impeachment moves against Governor Siminalayi Fubara, Tinubu pulled the state back from the edge of another self-inflicted crisis: legislative paralysis, executive uncertainty, and political instability in one of Nigeria’s most strategic states.

That intervention, in itself, is statesmanlike. Rivers cannot afford another season of emergency rule or a governance vacuum created by endless power tussles. Tinubu was right to draw a red line.

Nevertheless, leadership interventions are not judged only by intent; they are judged by logic, coherence, and long-term implications. In addition, it is here that Tinubu’s peace deal raises uncomfortable, even dangerous, questions about political authority, party structures, and the meaning of leadership itself.

The most contentious plank of the agreement, that Fubara must formally recognize Nyesom Wike as the “undisputed political leader” of Rivers State, may have halted impeachment threats, but it opens a deeper constitutional and political puzzle: “Can anyone truly be a leader in a vacuum?”

Wike is currently suspended from the Peoples Democratic Party, the platform on which he rose and over which he once held iron control in Rivers. He is not a card-carrying member of the All Progressives Congress in the state. Yet he is being elevated, by presidential fiat, to the position of final authority over party matters in Rivers, cutting across party lines. That is not political realism. That is political exceptionalism.

Political leadership does not exist in abstraction. It is anchored in structures: party membership, institutional legitimacy, electoral mandate, and constitutional responsibility. Strip those away, and what remains is influence, sometimes immense, sometimes coercive, but influence is not the same thing as leadership.

Tinubu’s directive effectively asks Rivers politics to suspend the rules of political gravity: to recognize a leader who does not formally belong to the ruling party in the state, is under disciplinary sanction in his own party, and holds no elective mandate in Rivers. yet wields veto power over its internal political processes.

That may work in the short term. It may even buy peace. However, it is not sustainable governance; it is crisis management by hierarchy.

The president reportedly drew parallels with Lagos, asking whether Babajide Sanwo-Olu is his leader in Lagos or whether Babatunde Fashola was his leader when he governed the state. The analogy is seductive, but flawed. Lagos operates within a disciplined party structure where authority, while layered, is clear. Rivers does not. Lagos has a single dominant party with defined internal chains of command. Rivers is now a political orphanage, governed by an APC president, administered by an APC governor, and supervised politically by a minister suspended from his party and unaffiliated with the ruling one. That is not leadership. That is managed contradiction, which brings us to a more troubling question: “Are governors still the number one party leaders in their states?”

Traditionally, Nigeria’s political culture answers that question with a resounding yes, for better or worse. Governors control party structures, dictate candidate selection, and determine political survival. That reality has often bred impunity, but it has also provided clarity. You knew who was in charge.

Tinubu’s Rivers intervention appears to upend that convention. Fubara remains governor, but not leader. He is chief executive, but not chief political authority. He is accountable for governance outcomes, yet stripped of final say over the party machinery that underpins his administration. That is a recipe for permanent instability.

No governor can govern effectively while perpetually negotiating legitimacy with a superior political authority operating from outside the state. It weakens executive confidence, blurs accountability, and invites endless proxy battles. Governance becomes transactional, not visionary.

Yes, Fubara owes his political emergence to Wike. Gratitude matters in politics. Respect for elders matters too. Nevertheless, gratitude is not the same as surrender, and respect does not require abdication of constitutional responsibility. Rivers State did not elect a caretaker; it elected a governor.

Tinubu was right to insist that Wike back off impeachment plots. Weaponizing impeachment is corrosive and destabilizing. However, the counter-demand that Fubara formally submit to Wike’s political supremacy, risks entrenching the very godfatherism Nigeria claims to be outgrowing.

Even more problematic is the reported instruction that APC structures in Rivers must recognize Wike’s preferred candidates for upcoming House of Assembly by-elections. That crosses from mediation into micromanagement of party autonomy. Political parties cannot function as rented platforms, deployed at will by individuals who do not formally belong to them.

If party membership no longer matters, if suspension carries no consequence, if leadership can be conferred without structure, then parties themselves become meaningless shells, mere electoral vehicles without ideology, discipline, or internal democracy.

To be clear, Tinubu’s broader objective, stability in Rivers ahead of 2027, is understandable. Rivers is politically and economically strategic. Chaos there weakens the centre. However, stability built on contradictions rarely lasts. It only postpones the reckoning.

Presidential authority cannot enforce leadership indefinitely. It must be rooted in legitimacy. In addition, legitimacy flows from structure.

If Wike is to be Rivers’ political leader, let it be clearly defined: through party alignment, formal roles, or negotiated consensus within an identifiable platform. Anything else turns leadership into a personal privilege rather than an institutional reality.

Tinubu has bought Rivers peace. That deserves applause. Nevertheless, peace is not the same as resolution.

The unresolved question remains: “Can a man suspended from his party, unaffiliated with the ruling one, and operating from Abuja truly be the political leader of a state and for how long?”

Until that question is honestly answered, Rivers State is not at peace. It is merely on pause.