Africa

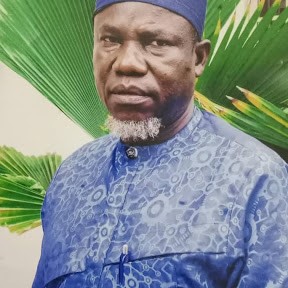

The Law Exists To Serve Society, Not To Oppress It – Barrister Abiodun Ogundare -By Isaac Asabor

Ogundare’s conclusion is blunt and unsentimental: democracy is not sustained by ballots alone. It is sustained by believable justice. When justice is accessible, citizens feel protected. When it is humane, they feel respected. Without both, democracy becomes either performative or oppressive.

In a country where the law is often spoken of in hushed tones, feared more than it is understood, Barrister Abiodun Ogundare is making a deliberate effort to demystify legal practice and return it to its original purpose: service to society. Calm, reflective, and firm in his convictions, Ogundare belongs to a growing but still rare class of legal professionals who see the courtroom not as a battlefield for ego or profit, but as a civic space where justice must be practical, humane, and accessible.

His decision to open a new law chamber is not driven by vanity or ambition in the conventional sense. It is, by his own account, a response to a moral obligation. For Ogundare, the law is not merely a career path; it is a responsibility, one that must be carried with conscience.

Opening a law chamber in today’s Nigeria is no small undertaking. Rising operational costs, slow judicial processes, and widespread public distrust in institutions make legal practice increasingly challenging. Yet Ogundare insists that the timing is deliberate.

For him, the chamber is not just an office; it is a structured platform to pursue justice, mentor young lawyers, and make legal knowledge available to people who often feel excluded from the system. He believes the legal profession has become too distant from the everyday realities of ordinary citizens, artisans, traders, low-income workers, who are most vulnerable to abuse and exploitation.

“The law should not be an exclusive club,” he argues. “When people feel shut out from justice, society becomes unstable.”

One of the most striking observations Ogundare makes is that the greatest barrier between citizens and the law is not ignorance, but fear. Many people, he notes, know something is wrong when their rights are violated, but they are intimidated by legal language, procedures, and the perceived arrogance of practitioners.

By simplifying legal information, encouraging early consultations, and speaking plainly rather than in legal jargon, Ogundare hopes to bridge the psychological gap that keeps many Nigerians away from seeking help. In his view, understanding one’s rights and obligations does more than resolve disputes; it promotes peaceful coexistence and responsible citizenship.

Perhaps the most defining feature of Ogundare’s practice is his commitment to pro bono legal services. In a system where justice often appears transactional, he insists that access to legal protection should not depend solely on one’s financial capacity.

Free legal services, he explains, are extended to indigent clients, vulnerable persons, and cases that touch directly on human dignity. These include matters involving unlawful detention, domestic abuse, child protection, and situations where one party is clearly disadvantaged by poverty or social status. Each case is assessed on its merit, not sentiment.

The broader impact, he believes, is societal. Pro bono work reduces injustice, prevents conflicts from escalating, and builds trust in the legal system. When people feel heard and protected, social cohesion improves. Justice, in this sense, becomes preventive rather than reactive.

Ogundare is quick to challenge the notion that legal service begins and ends in court. Litigation, he argues, is often the last resort. True service includes legal education, policy advocacy, alternative dispute resolution, and sustained community engagement.

In many cases, preventing a dispute through timely legal advice is more impactful than winning a case after damage has already been done. This approach reflects his belief that lawyers are not merely problem-solvers, but also custodians of social order.

In an era when public confidence in institutions is fragile, Ogundare places integrity at the center of legal practice. Without it, he says, the law loses its moral authority and becomes just another instrument of power.

For him, integrity means being guided by conscience as much as by statutes and case law. It requires honesty with clients, respect for ethical boundaries, and the courage to say no, even when compromise might be more profitable.

Balancing professional obligation with compassion, he adds, does not mean bending the rules. It means listening attentively, explaining options truthfully, and acting in the client’s best lawful interest.

To individuals facing legal challenges but hesitant to seek help, Ogundare’s message is direct: silence is often more damaging than the problem itself. Early consultation, formal or informal, can prevent irreversible mistakes.

Looking ahead, Ogundare’s vision for his chamber is grounded and unpretentious. He wants to build a practice known for professionalism, ethical consistency, and service to humanity. Success, in his view, is not measured solely by cases won, but by lives positively impacted.

He also places strong emphasis on legal literacy, especially among young people and communities. Understanding basic rights, contracts, civic duties, and dispute resolution mechanisms empowers citizens and reduces exploitation. An informed society, he believes, is a safer and fairer one.

At the heart of Ogundare’s philosophy is a powerful idea: justice is the oxygen of democracy. Without accessible and humane justice, democratic institutions become hollow rituals, elections without accountability, laws without legitimacy, and governance without trust.

Accessible justice, he explains, makes power answerable. Democracy assumes that authority can be questioned, and courts provide citizens with a practical way to challenge abuse by the state, corporations, or individuals. Where justice is distant or cruel, impunity thrives.

Humane justice turns rights from paper into reality. Constitutions are meaningless if citizens cannot enforce them without humiliation or prohibitive cost. When people see their rights upheld fairly, democracy gains credibility.

Fair justice also builds public trust. Societies do not revolt because laws exist; they revolt when laws are selectively applied. Compassionate and impartial justice signals that institutions work for everyone, not just elites.

Equally important, accessible justice prevents self-help and lawlessness. When courts are unreachable, citizens resort to vigilante action, mob justice, or bribery. Humane justice keeps conflict within institutional boundaries rather than spilling into the streets.

It protects minorities and dissenters, reminding society that democracy is not majority tyranny. It encourages civic participation by assuring citizens that the system listens. And it keeps leaders within legal limits, making accountability preventive rather than reactive.

Ogundare’s conclusion is blunt and unsentimental: democracy is not sustained by ballots alone. It is sustained by believable justice. When justice is accessible, citizens feel protected. When it is humane, they feel respected. Without both, democracy becomes either performative or oppressive.

In a legal culture too often accused of serving power rather than people, Barrister Abiodun Ogundare’s stance is clear and uncompromising: the law exists to serve society, not to oppress it.