Africa

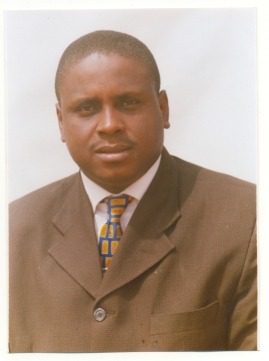

What a Proper Police Commissioner Would Have Done in Kurmin Wali: The Normal Police Moves Muhammad Rabiu Refused to Make -By Professor John Egbeazien Oshodi

But what makes Kurmin Wali different is the speed and cruelty of the denial. It came too quickly, too confidently, too arrogantly, as though he already knew the script: deny, intimidate, demand names, and shut the story down. That reflex is what proves the system is sick, because a healthy system responds to crisis with protection, not performance.

In a Normal Country, This Would Have Been Treated as a National Emergency, Not a Rumour

When armed men invade churches during worship and force people into the forest, the response of a serious police command is not debate. It is not denial. It is not press bravado. It is emergency action. That is the global standard. It is how policing is supposed to work in any normal security climate where law enforcement still respects human life and understands that time is the difference between rescue and regret.

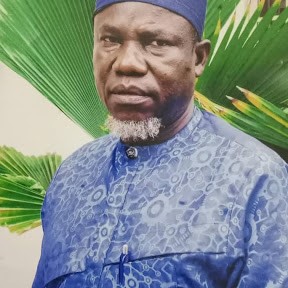

But Nigeria is battling a painful abnormality that has become too familiar: many citizens have been conditioned to expect denial before rescue, dismissal before empathy, and argument before action. In Kurmin Wali, the tragedy did not only happen in the forest. It also happened in the mouth of authority. The Kaduna State Police Commissioner, Muhammad Rabiu, did what the system has been trained to do too often: lie fast, dismiss quickly, and protect government comfort before protecting endangered citizens. The speed of the denial is what makes it especially horrifying. Not only did the denial come, it came like an automatic reflex, as if truth was the enemy that needed to be neutralized immediately.

This is why Kurmin Wali should not be treated as another passing outrage. It is a clinical case study of institutional decay. It is what happens when a police command is more psychologically loyal to government image than to human life. And it is why Nigerians must insist on a standard that has long been neglected: in proper policing, the first duty is operational response, not narrative control.

The Standard of Real Policing: Act First, Speak Carefully, Then Update Publicly

Proper policing is built on a crisis logic that is simple and universal. When distress reports emerge, you do not begin by insulting the public. You do not begin by labeling witnesses. You do not begin by calling citizens conflict entrepreneurs. You begin by acting, because action protects life while communication maintains public order.

In a normal climate, the commissioner would have activated emergency response immediately while releasing a cautious statement: reports have been received, response is underway, verification is ongoing, and citizens should cooperate and stay alert. That kind of statement does not weaken government. It strengthens public trust. It tells the public the police are listening, not fighting. It signals to criminals that the state is moving, not debating.

What Rabiu did was the opposite. He denied first. That is what a weak system does when it feels exposed. The problem is that denial might protect reputation for one hour, but it destroys rescue probability for many hours. And in kidnapping operations, hours matter more than excuses.

First Move: Issue an Emergency Confirmation Statement, Not a Dismissal Statement

A proper police commissioner never rushes to call citizen reports “falsehood.” Muhammad Rabiu did. He described the abduction report as “a falsehood being peddled by conflict entrepreneurs seeking to cause chaos in the state.” That is not crisis leadership. That is hostile communication toward the public at the worst possible moment.

In a normal country, the commissioner would have said: we have received reports, our teams are deployed, and we will confirm details shortly. That one sentence alone would have reduced panic, invited cooperation, and increased intelligence flow. Instead, denial shut the public down. It created fear of speaking. It created fear of being labeled. It created fear of being threatened with “the full weight of the law.”

This is why the denial was not only wrong, it was dangerous. It framed community alarm as sabotage, not as survival information.

Second Move: Immediate Deployment of Rapid Response and Tactical Units

In functional policing, the first hour is treated like a rescue window. The commissioner would have deployed tactical units, mobile police forces, counter kidnapping structures, and joint teams with the military. If roads were poor, that would not be an excuse to slow down. It would be the reason to intensify and improvise.

Vanguard’s report indicates the area is remote and hard to access due to bad roads. In proper policing, that detail triggers alternative strategy: approach routes from multiple angles, use local guides, deploy motorcycles where vehicles fail, coordinate aerial surveillance where available, and create rapid pursuit pathways.

A proper commissioner would have treated the terrain as a challenge to overcome, not as a reason to hesitate. He would have understood that kidnappers exploit geography. They pick remote places for one reason: delay. That is why the police must move as if delay is a weapon in the kidnappers’ hands.

Third Move: Establish a Forward Command Post and Incident Commander Immediately

In serious crisis response, you do not manage a mass abduction from a conference room. You establish a forward command post close enough to feel the community’s fear and fast enough to receive real time intelligence.

A forward command post means one thing: control. It means there is an incident commander on ground, coordinating search units, intelligence flow, rescue routes, medical preparedness, and witness management. It means decisions are made with speed. It means rescue becomes structured rather than chaotic.

And it sends a psychological message. The police are present. The state is not hiding. The uniform has not become a speech tool only. The state is close enough to bleed with the people.

That is what the uniform symbolizes. Not denial. Presence.

Fourth Move: Secure Survivors, Stabilize Trauma, and Stop the Panic Spread

Kurmin Wali was described as deserted. Survivors fled to nearby communities to stay with relatives and friends. People sustained injuries and remained in shock. Poor network coverage and lost phones made contact difficult.

In normal policing, a mass abduction triggers immediate victim support protocols. You protect those who escaped, because they are both survivors and witnesses. You provide medical triage. You provide secure safe zones. You coordinate transport for injured persons. You deploy patrols around surrounding areas to prevent follow up raids.

You also calm panic. Panic spreads like fire in vulnerable communities. When panic spreads, families scatter, information breaks apart, and intelligence becomes fragmented. A proper police command stabilizes the environment so reporting can continue and rescue can be guided by real time facts.

A denial based command does the opposite. It increases panic because people realize they may be abandoned twice: first by the criminals, then by the state.

Fifth Move: Build the Missing Persons List as a Police Duty, Not a Public Challenge

This is where the Kurmin Wali story becomes a moral disgrace. Muhammad Rabiu demanded a list of kidnapped persons and their particulars as if the public must prove suffering before police act.

In proper policing, the list is not a public dare. It is an operational tool created by the police immediately. The commissioner would have ordered officers to go house to house, church to church, family to family, collecting names, ages, photos, contact information, and last seen descriptions.

That missing persons register would then drive the rescue operation. It would allow the police to know exactly who is missing, how many children, how many women, how many elderly, which households have been emptied, and where to focus communication.

But Nigeria’s broken system often reverses responsibility. Instead of the police producing facts, they challenge citizens to produce facts. That is not policing. That is institutional laziness wrapped in authority.

Sixth Move: Activate Intelligence and Track Movement Immediately

Kidnapping is not only violence. It is logistics. The kidnappers must move people, feed people, hide people, and communicate demands. A proper commissioner understands that every kidnapping group leaves a trail.

The trail includes motorcycle tracks, footpath patterns, forest routes, informant whispers, and communication signals. A proper police command would immediately activate intelligence collection and route mapping. They would work with local residents who understand the terrain. They would block likely escape paths. They would expand operational radius to prevent the kidnappers from settling in a safe zone.

In the Kurmin Wali case, the police situation report cited difficulty in access and ongoing effort. But public denial undermines intelligence. Communities cannot feed intelligence to a command that first calls them liars.

Seventh Move: Treat Community Leaders as Partners, Not as Instruments of Denial

In a normal climate, community leaders are engaged as allies. They are not recruited as props to calm embarrassment. They are not used to create a false impression of peace. They are not used to deny suffering.

A proper commissioner would meet with church leaders, elders, youth coordinators, and local heads with one aim: gather facts, coordinate safety, and build trust.

Trust is a policing asset. Once trust collapses, citizens stop reporting, stop cooperating, and begin to protect themselves privately. That is how criminal networks expand. That is how insecurity becomes permanent.

Denial destroys trust. It announces that the state is not a partner. It is a critic.

Eighth Move: Daily Briefings With Verified Facts, Not Threats

A proper police command would provide daily briefings with verified facts: how many missing, how many rescued, what efforts are underway, what hotlines exist, and how families can report useful information.

This does not expose operations. It builds confidence. It reduces rumor. It strengthens cooperation. It separates facts from fear.

But when a commissioner leads with denial and threats, the public learns to distrust updates. They begin to treat official statements as political defense rather than public safety information. That is the real collapse. When citizens stop believing official communication, the state has lost the psychological war of legitimacy.

Ninth Move: Preserve Evidence and Treat the Churches as Crime Scenes

A proper command treats the churches as crime scenes. Even in rescue focus, evidence matters. Shell casings, entry paths, footprints, patterns of movement, and witness statements all build future prosecution.

When the state denies the incident, evidence collection becomes delayed. Delayed collection means contamination. Contamination means fewer arrests. Fewer arrests mean criminals become bolder. That is how denial produces more crime.

Tenth Move: Show Humility, Not Arrogance

In crisis leadership, humility is a tool. It is not weakness. It tells citizens their pain is respected. It tells victims they are seen. It invites witnesses to speak. It creates psychological safety for reporting.

Muhammad Rabiu did not show humility. He dismissed. He challenged. He labeled. That is why he failed not only operationally, but psychologically. Because security is not only weapons and vehicles. Security is trust and truth. Once trust is broken, security cannot function.

The Larger System: Rabiu Was Doing What the System Does, but He Did It Too Fast and Too Cruelly

Now we come to your deeper point, and it is the most painful truth Nigerians must face. Muhammad Rabiu was not inventing a new tradition. He was practicing the tradition Nigeria has allowed to grow. The tradition of quick denial. The tradition of dismissal. The tradition of hiding. The tradition of treating citizens like enemies of state image.

But what makes Kurmin Wali different is the speed and cruelty of the denial. It came too quickly, too confidently, too arrogantly, as though he already knew the script: deny, intimidate, demand names, and shut the story down. That reflex is what proves the system is sick, because a healthy system responds to crisis with protection, not performance.

That is why this moment must become a national lesson. Nigeria must stop tolerating officials who act like public relations defenders of government rather than guardians of citizens. Nigeria must stop allowing uniformed leaders to treat human disappearance as a rumor problem.

The Global Damage: Denial Travels Faster Than Rescue

Vanguard published the names of 177 abducted worshippers. International attention followed, including condemnation from United States lawmaker Representative Riley Moore urging swift and safe return of the abducted.

This is how Nigeria loses credibility. A tragedy happens, denial happens, names appear, foreign voices speak, and Nigeria looks unserious. The world does not only judge kidnapping. The world judges the response. And denial is the worst response because it makes the government look complicit in silence.

Final Word: A Commissioner Who Denies Victims Cannot Lead a Rescue Culture

A proper police commissioner would have acted first and spoken carefully. Muhammad Rabiu spoke first and denied.

A proper police commissioner would have built a missing persons register as a police responsibility. Muhammad Rabiu demanded the list as though citizens must prove their own disappearance.

A proper police commissioner would have treated Kurmin Wali as an emergency. Muhammad Rabiu treated it as an embarrassment to be managed.

And that is why he must not wear that uniform for another minute.