Forgotten Dairies

Reimagining African Pharmacy Through Afrofuturism -By Patrick Iwelunmor

Reimagining African pharmacy through Afrofuturism is not fantasy. It is disciplined imagination applied to structural reform. It calls on pharmacists to see themselves not merely as custodians of imported supply chains, but as architects of innovation. It calls on policymakers to treat pharmaceutical manufacturing as strategic infrastructure equal to energy or defense. It calls on educators to cultivate scientific curiosity alongside institutional courage.

Africa stands at a pharmaceutical crossroads. This is not an abstract metaphor. It is visible in hospital corridors where essential medicines are out of stock, in rural pharmacies where patients are told to “check back next week,” and in the quiet frustration of pharmacists who understand the science but lack the infrastructure to practice it fully. Endowed with immense medicinal flora and fauna, rich therapeutic traditions, and a youthful scientific workforce, the continent should not occupy the margins of global pharmacy practice. Yet it does.

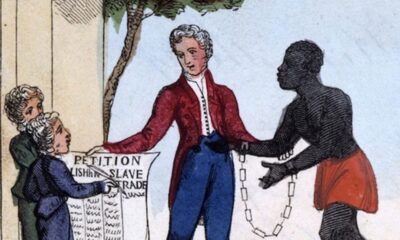

The paradox is stark. African ethnobotany has shaped global drug discovery for centuries, yet African nations continue to import between 70 and 90 percent of the medicines they consume. Africa consumes what it could invent, dispenses what it could discover, and regulates what it did not formulate. Reimagining African pharmacy is therefore not a vision, it is an urgent imperative.

That reimagination demands an Afrofuturist lens. Popularly associated with cultural expressions such as the 2018 Marvel film Black Panther, Afrofuturism is far more than aesthetic spectacle. It is a philosophical repositioning that insists African knowledge systems, institutions, and innovations occupy central space in shaping the future. It resists epistemic marginalization and interrogates inherited hierarchies of scientific authority. It asks a simple but disruptive question, what does the world look like when African agency is foundational rather than peripheral?

This intellectual repositioning is grounded in scholarship. Professor Toyin Falola has long argued for narrative sovereignty and intellectual self-determination, the insistence that African societies must define the frameworks through which their knowledge is understood and deployed. His work reminds us that African epistemologies were not deficient, they were displaced. Afrofuturism extends that reclamation into the future. In pharmacy, this means refusing to treat indigenous medicinal knowledge as folklore. It means recognizing it as a legitimate foundation for scientific exploration, technological refinement, and institutional design.

Applied to practice, intellectual sovereignty must translate into industrial capacity. Pharmaceutical sovereignty requires deliberate policy architecture, continental pooled procurement mechanisms to strengthen bargaining power, coordinated regulatory harmonisation under the African Medicines Agency, targeted manufacturing corridors within the African Continental Free Trade Area, and strategic investment funds dedicated to pharmaceutical infrastructure. Without such structural instruments, vision risks remaining rhetorical.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of Africa’s dependency model. Vaccine inequity left many nations negotiating from positions of urgency rather than strength. Yet the crisis also revealed possibility. The establishment of mRNA vaccine manufacturing capacity at institutions such as the Biovac Institute demonstrated that advanced pharmaceutical production is achievable on African soil when political will aligns with investment. Excellence, in other words, is not geographically predetermined, it is infrastructural, strategic, and intentional.

Nowhere is this reimagination more compelling than in ethnobotany. Africa’s forests and savannahs contain thousands of medicinal plants with documented therapeutic properties. The United Nations Environment Programme has affirmed the depth of indigenous ecological knowledge across the continent. For generations, traditional healers developed precise understandings of plant chemistry, dosage patterns, and environmental rhythms. Many pharmacists today were first introduced to healing through community-based herbal knowledge before formal scientific training refined that understanding.

An Afrofuturist approach does not romanticize traditional medicine, nor does it dilute scientific rigor. It integrates both. It insists on pharmacognosy, biotechnology, clinical validation, patent protection frameworks, and robust quality assurance systems. It envisions collaborative research ecosystems where traditional practitioners, pharmacists, chemists, and molecular biologists co-create innovation. It asks, with disciplined seriousness, why should the next global phytopharmaceutical breakthrough not be patented, produced, and exported from African soil?

The epidemiological realities intensify this imperative. Sub-Saharan Africa bears a disproportionate share of the global burden of infectious diseases, including the majority of malaria deaths, according to the World Health Organization. Meanwhile, non-communicable diseases are rising steadily. For families navigating hypertension, diabetes, or recurrent malaria, pharmaceutical dependency is not theoretical, it is immediate. Pharmaceutical sovereignty, therefore, is not ideological ambition; it is a public health necessity.

For decades, global narratives have cast Africa as a site of medical intervention rather than pharmaceutical invention. Shifts in foreign health funding priorities, including decisions by U.S. President Donald Trump affecting agencies such as USAID, underscore how vulnerable external dependency can be. But vulnerability clarifies responsibility. Sustainable pharmaceutical systems cannot rest on fluctuating geopolitical goodwill. They must be anchored in domestic investment, regulatory confidence, continental coordination, and long-term scientific ambition.

Reimagining African pharmacy through Afrofuturism is not fantasy. It is disciplined imagination applied to structural reform. It calls on pharmacists to see themselves not merely as custodians of imported supply chains, but as architects of innovation. It calls on policymakers to treat pharmaceutical manufacturing as strategic infrastructure equal to energy or defense. It calls on educators to cultivate scientific curiosity alongside institutional courage.

The future of pharmacy need not be written elsewhere. By harmonizing indigenous knowledge with rigorous validation, biodiversity with biotechnology, and imagination with policy design, Africa can move from the periphery to the center of pharmaceutical innovation. Afrofuturism, in this context, becomes more than a cultural framework; it becomes a strategic doctrine. And if Africa commits to that doctrine with institutional seriousness, the question will no longer be whether African pharmacy can lead, but how quickly it will transform the health of the continent and redefine global science itself.

For Nigerian pharmacists, the challenge is also an opportunity. You are not merely dispensers of imported medicines, you are custodians of knowledge, innovators in waiting, and architects of Africa’s pharmaceutical future. Every laboratory experiment, every clinical observation, and every integration of indigenous wisdom is a step toward sovereignty and global recognition. Afrofuturism invites you to imagine boldly, to collaborate across disciplines, and to claim your rightful place not at the margins, but at the center of discovery, policy, and innovation. The future of African pharmacy is not written elsewhere; it is being built by those willing to envision, design, and execute it here at home.